Trump Calls for Barack Obama’s Arrest - Though the Only U.S. President Ever Arrested

|

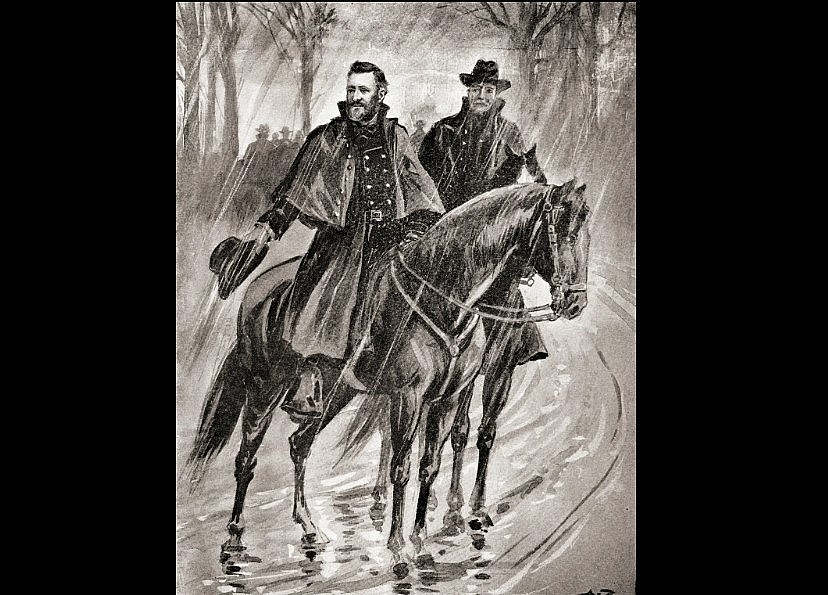

| Grant on horseback in the rain before the battle in Belmont, Missouri in 1861 (Universal Images Group via Getty Images) |

After Donald Trump publicly called for the immediate arrest of former President Barack Obama, a familiar question resurfaced in American political debate:

Has a U.S. president ever actually been arrested?

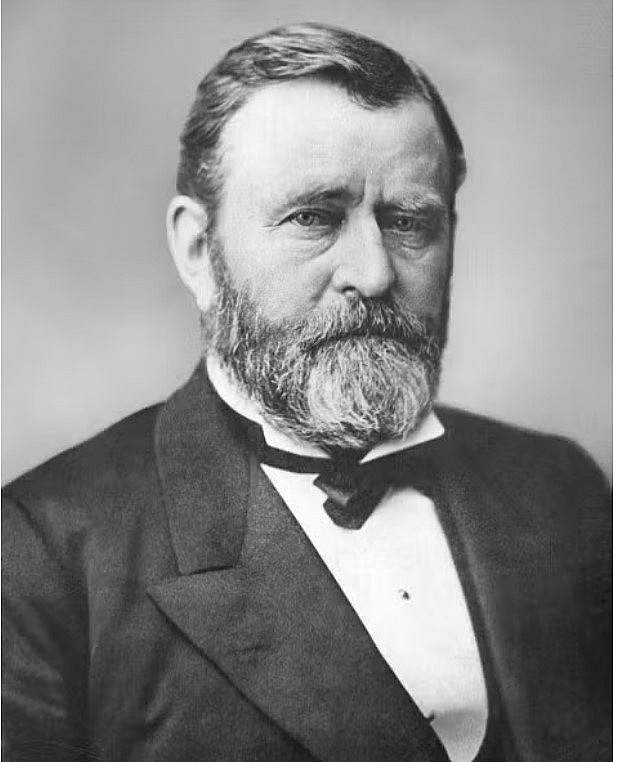

The answer, often cited but rarely explained correctly, points to a single, unusual episode from the 19th century. In 1872, Ulysses S. Grant, while serving as president, was arrested in Washington, DC—not for corruption or abuse of power, but for speeding in a horse-drawn carriage.

The story sounds almost humorous by modern standards. Yet it is real, documented, and often misunderstood. More importantly, it reveals how carefully American law has always separated symbolic enforcement of the law from dangerous political precedent.

Read more: Top 11 Historic Restaurants U.S. Presidents Have Visited Outside the White House

What actually happened in 1872

|

| President Ulysses S. Grant’s Need for Speed Led to His 1872 Arrest |

Grant, a Civil War general known for decisiveness and intensity, enjoyed driving fast horses through the streets of Washington. According to historical accounts, local police officers had warned him repeatedly about riding too quickly and endangering pedestrians.

On one occasion, after Grant ignored those warnings, a police officer stopped him and formally placed him under arrest for violating local traffic ordinances.

Key details matter here:

-

Grant was not handcuffed.

-

He was not jailed.

-

He did not resist or invoke presidential privilege.

-

He was taken briefly to the station, signed a promise to appear in court, and was later fined, like any other citizen.

The officer knew exactly who Grant was. This was not confusion or mistake. It was a conscious act of enforcing local law against the highest official in the country.

What “arrest” meant in the 19th century

In modern usage, “arrest” usually implies criminal detention, prosecution, and potential incarceration. In 19th-century America, especially for minor offenses, the term was far broader.

Grant’s arrest was:

-

Procedural, not punitive

-

Administrative, not criminal

-

Intended to ensure court appearance, not deprivation of liberty

Legally speaking, this was closer to a traffic citation than a criminal arrest as understood today.

Is this a legal precedent for arresting a president?

No. And this point is critical.

Despite frequent references to the Grant episode, it has never been treated as a constitutional or legal precedent. Here’s why:

1. No conflict with presidential duties

Grant’s brief detention did not interfere with executive authority or national governance. There was no constitutional crisis.

2. No criminal charges

The offense was minor and personal, unrelated to official acts or abuse of power.

3. No judicial reliance

American courts, the Department of Justice, and constitutional scholars have never relied on this case when discussing presidential immunity or criminal liability.

In legal scholarship, the incident is often described as a historical anecdote with symbolic value, not a guiding case.

What the Grant arrest really demonstrates

Although it lacks legal force, the episode still matters.

It illustrates a deeply American principle: the rule of law applies socially, even when constitutional limits apply institutionally.

Grant accepted the stop, the fine, and the process. The officer enforced the law without theatrics or political motive. Neither side attempted to turn a minor infraction into a test of power.

That restraint is the real lesson.

Why this story keeps being misused today

Modern political debates often cite Grant’s arrest to argue that any president or former president can be arrested at any time.

That leap is misleading.

Grant’s case:

-

Did not involve criminal prosecution

-

Did not involve imprisonment

-

Did not involve actions taken as president

Using it to justify aggressive criminal action against political leaders today ignores two centuries of constitutional caution and legal evolution.

The Bottom Line

Ulysses S. Grant remains the only U.S. president ever arrested, but only in the narrowest, most technical sense of the word.

His 1872 speeding arrest was:

-

✔ Real

-

✔ Documented

-

✔ Symbolically powerful

But it was not a precedent for criminally arresting a sitting president, and it was never meant to be.

The story endures not because it authorizes future arrests, but because it reflects something rarer: a system confident enough to enforce small laws without weaponizing them.