British National Anthem: Full Lyrics and History of "God save the Queen"

|

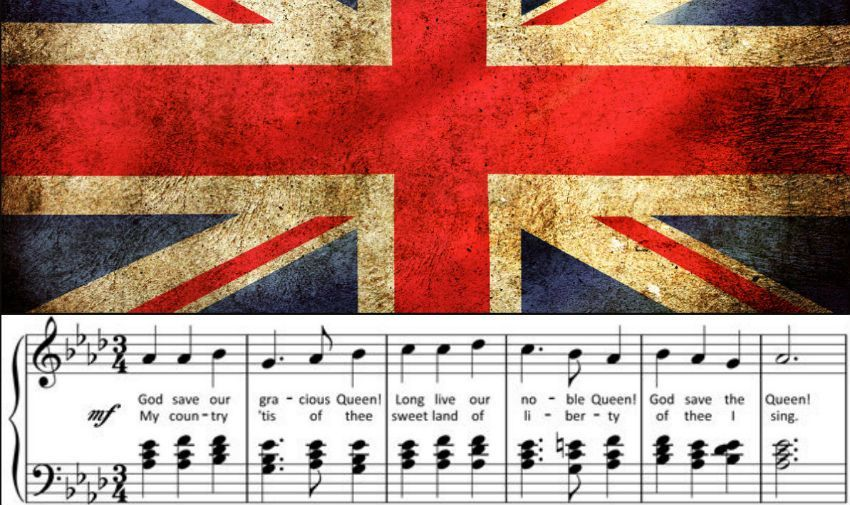

| "God Save the Queen" - Full Lyrics of British National Anthem |

The national or royal anthem of several Commonwealth realms, their territories, and British Crown dependencies is "God Save the Queen" (or "God Save the King," depending on the gender of the current monarch). Several Commonwealth of Nations members, like Malaysia, do not have a royal anthem or have a different one than the one used by the United Kingdom.

Although its roots in plainchant cannot be ruled out, the tune is often credited to the composer John Bull, who may or may not have written it.

"God Save the Queen" is the de facto national anthem of the United Kingdom and one of two national anthems used by New Zealand since 1977, as well as for several of the UK's territories that have their own additional local anthem.

In addition to being the national anthem of the aforementioned countries, it is also the royal anthem of Australia (1984), Canada (1980), and the vast majority of other Commonwealth realms. Nonetheless, the national anthem is played instead in Barbados.

Full lyrics of "God Save The Queen" - British National Anthem

God save our gracious Queen,

Long live our noble Queen,

God save the Queen:

Send her victorious,

Happy and glorious,

Long to reign over us:

God save the Queen.

O Lord our God arise,

Scatter her enemies,

And make them fall:

Confound their politics,

Frustrate their knavish tricks,

On Thee our hopes we fix:

God save us all.

Thy choicest gifts in store,

On her be pleased to pour;

Long may she reign:

May she defend our laws,

And ever give us cause

To sing with heart and voice

God save the Queen.

Watch lyrics video of "God Save The Queen" - British National Anthem below:

God Save the Queen: The History of the National Anthem

While the song's backstory is shrouded in mystery, there is no disputing the fact that "God Save the Queen" as we know it today saw a meteoric rise to popularity in the month of September 1745. Throughout that month, public displays of support for the monarchy were especially sought after. London was getting ready to defend itself and its Hanoverian overlords from an impending invasion by Charles Edward, the Young Pretender, who had just defeated Cope at Prestonpans. On September 28th, for example, the whole male ensemble of the Drury Lane theater announced their intention to establish a special unit of the Volunteer Defense Force, demonstrating the widespread support for the cause. They performed The Alchemist by Ben Jonson that night. It wrapped up with an extra component. Mrs. Cibber, Beard, and Reinhold, three of the most famous singers of the day, took the stage and began to sing a particular anthem.

“God bless our Noble King,

God Save great George our King ...”

The universal applause sufficiently denoted in how just an Abhorrence they (the audience) hold the Arbitrary Schemes of our invidious enemies. ...” The other theatres were quick to follow Drury Lane. Benjamin Victor, the linen merchant, wrote to his friend Garrick, who was ill in the country: “The stage is the most loyal place in the three kingdoms,” and Mrs. Cibber noted: “The Rebellion so far from being a disadvantage to the playhouses, brings them very good houses.” Soon the anthem was being sung as far afield as Bath.

Neither words nor music were new. They had been published in 1744 in the Thesaurus Musicus. Dr. Thomas Arne compiled Drury Lane’s version in September 1745, and one of his younger pupils, Charles Burney, produced the setting for Covent Garden. Sixty years later, the eminent Dr. Burney recalled some interesting facts about the origins of the anthem for the benefit of his friend Sir Joseph Banks, the naturalist. Burney, in common with all contemporaries dealing with the 1745 versions, referred to an “old tune” and an “old anthem.” He continued:

“Old Mrs. Arne, the mother of Dr. Arne and Mrs. Cibber, a bigotted Roman Catholic, said she had heard it sung not only at the playhouse but in the street when the Prince of Orange was hovering over the coast.”

On a later occasion Burney was more definite:

“the earliest copy of the words we are acquainted with begin—God Save Great James Our King. I asked Dr. Arne if he knew who the composer was: he said he had not the least knowledge ... but that it was a received opinion that it was written and composed for the Catholic Chapel of James II.”

In all likelihood, this will occur. Musicologists have tracked the tune all the way back to a medieval plainsong chant, through a carol, and finally to an Elizabethan composer named John Bull. Purcell wrote a few bars at the end of the seventeenth century that are nearly indistinguishable from the first phrases of the Arne and Burney arrangements. To my knowledge, neither Henry Carey nor the French composer Lully had any part in the music.

Given the inherent loyalty implied by the words, pinpointing when they were first spoken is an impossibility. Several times in the earliest English Bible translations, the phrase "God Save the King" appears. God Save King Henry and Long to Reign Over Us were designated as the watchword and counterword, respectively, in an Order of the Fleet issued at Portsmouth on August 10th, 1544. Since Queen Elizabeth's coronation, the phrase "God Save the Queen" has marked the conclusion of royal proclamations. The phrases "scatter our enemies" and "confound their devices" can be found in many loyal prayers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries for the Sovereign and the State, and are echoed in the national anthem. The song "God Save the King" had likely settled into its standard form by the time of King James II. An early eighteenth-century Latin translation of the work was discovered and is thought to have been written for use in his Catholic chapels, though this is pure conjecture. After the Revolution, the song became identified with support for the Hanoverian monarchy.

It was not yet, of course, the National Anthem. Such a concept would have been incomprehensible to the eighteenth cenutry. But within a year or so of 1745 it was being played and sung whenever Royalty appeared in public. Later in the century, Fanny Burney describes a visit with the Court to Cheltenham:

“All the way upon the road we rarely proceeded five miles without encountering a band of the most horrid fiddlers, scraping “God Save The King,” with all their might, out of time, out of time, and all in the rain ...”

Oddly enough, although it was loyal, it was not yet regarded as sacred music. At Lyndhurst, in 1789, Fanny Burney attended the Parish Church to give thanks for her Monarch’s recovery from one of his bouts of lunacy.

“After the service, instead of the psalm, imagine our surprise to hear the whole congregation join in ‘God Save The King.’ Misplaced as this was in a church, it’s interest was so kind, so loyal and so affectionate, that I believe there was not a dry eye. ...”

Miss Burney has also recorded some of the best-known occasions on which the anthem was played:

“At Weymouth God Save The King is inscribed on the hats and caps of children, all the bargemen wear it in cockades; and even the bathing women have it in large coarse girdles round their waists. The King bathes and with great success; a machine follows the Royal one into the sea filled with fiddlers who play ‘God Save The King’ as His Majesty takes his plunge!”

When Hadfield attempted to kill George III in the Theatre Royal on a May night in 1800, the national anthem was being sung at the time. Sheridan spontaneously composed a special extra verse to express the people's gratitude for Providence's benign intervention. However, "God Save the King" was not regarded as a sacred melody during the Regency or under George IV. The first time it was sung was at the coronation of George IV, though some of the churchgoers in the Abbey sang "God Save The Queen" to express their sympathies regarding the Royal Divorce.

William IV listened to an odd performance when he and Queen Adelaide opened the new London Bridge in 1831. They dined in the middle of the structure, and during the meal an official glee-party, under Sir George Smart, rendered musical honours, including “God Save The King.” To Smart’s consternation, a man and a woman walked forward,

“he playing ‘God Save The King’ with his knuckles on his chin, accompanied by his wife’s voice. The King called to me and asked me who they were. I told him I was sorry they had intruded without permission. ‘Oh, no. No intrusion ’ said the King. ‘It was charming. Tell them to perform it again.”

After the accession of Queen Victoria it is regularly referred to as the National Anthem, though the Queen seems to have regarded it as a family anthem as well, for special verses were produced for royal births and marriages.

Probably it was in foreign countries that the National Anthem was first included in collections of hymns. It is believed to be the first example of its particular metre in any European language—6.6.4.6.6.6.4. Once it had established itself in popular fancy, it was bound to spread. Numberless hymn-writers employed the metre, and before the eighteenth century was out, suitable national words had been composed for the time in Holland and Denmark, and many German States had adopted for their own Schumacher’s verse beginning “Heil dir im Sieger-kranz.” Russia used the tune until 1833, and Sweden and Liechtenstein are two other states who have set their own words to the music. The Swiss have no National Anthem, but they have written both French and German words to the melody. The American version “My Country ’Tis of Thee” appeared in 1831. Among composers, Haydn was a great admirer of “God Save The King,” and was instructed to compose something on the same lines when commissioned to write the Emperor’s Hymn— better known today in its later form of Deutschland Ueber Alles. Beethoven declared “I must show the English what a blessing they have in ‘God Save The King'. He wrote several variations on the tune and included the theme in his tribute to Wellington, The Battle. Weber used the melody at least twice, and Brahms wove it into his Triumphlied. J. C. Bach and Liszt are among many others who improvised on the anthem.

Since its first popularity in 1745, endless attempts have been made to improve the words. In December of that year the Gentlemen’s Magazine declared “the words have no merit but their loyalty” and offered its own new version, "Fame, let thy trumpet sing.” But the public stuck to Arne and Burney. In these settings there was no ambiguity about one’s loyalty— “Great George,” “On him our hopes are fixed,” “Scatter his enemies,” “May he defend our laws.” With the omission of one stanza referring to Marshal Wade “crushing rebellious Scots',” the 1745 Anthem remains substantially the accepted version today. It is a curious fact that an official version seems never to have been laid down. Longfellow’s improving lines were included in a Jubilee rendering for Queen Victoria:

“Lord, let war’s tempest cease

Fold the whole world in peace

Under thy wings.”

The Privy Council approved a "Peace Version" of the National Anthem in 1919, and it is now found in some hymnals. The National Anthem does not contain the words to the tune that are sung, as Mr. Philip Snowden, the Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time, stated in the House of Commons in 1931. Only the music itself qualifies as the national anthem. Regardless of how this may be, the final and most accurate arbiter on the singing of "God Save the Queen" does anticipate it being done so in accordance with the accepted lyrics. The appropriate section of the Army's Queen's Regulations is as follows:

“The authorized arrangement of the National Anthem as published by Messrs. Boosey and Hawkes Ltd. will invariably be used and will be rendered in the following style:

“The first bars will be played pianissimo at M.M. 60 crotchets, using the full reeds, horns and basses ... (the brass will be brought smartly into playing position on the third beat of the fifth bar) ... The comets and the side drum will be added on the second beat of the sixth bar... . The last eight bars will be played fortissimo as broadly as possible... . For singing, the key of ‘F’ will be used.”

British National Day

British National Day is a proposed official national holiday for the UK that would honor everything that is uniquely British. The UK currently lacks a single recognized national holiday, though the Queen's Official Birthday is occasionally used in place of one.

UK doesn't have a special national holiday. There are some holidays that are hardly ever observed and others that are connected to the nations that make up the United Kingdom. The latter category includes St. Patrick's Day in Northern Ireland, St. David's Day in Wales, St. Andrew's Day in Scotland, and St. George's Day in England.

The Queen's Official Birthday is currently observed as a de facto national day by British embassies abroad but not in the UK.

Full Lyrics of India’s National Anthem

Check out full lyrics of India's national anthem in short and long versions.

Full Lyrics of Singapore’s National Anthem

Listen to Onward Singapore-the national anthem of Singapore with a lyrics video to sing along.

Full Lyrics of Ireland’s National Anthem

Today, the English version of the Ireland anthem is rarely used, and many people are not aware that the Irish version was not the original ...

Full Lyrics of Malaysia’s National Anthem

Negaraku (meaning My Country in Malay) is the national anthem of Malaysia. How was it composed? What is the meaning of the song?