J.D Vance in the Marine Corps: 3 Names, 4 Years and Some Awards As Journalist

On July 15, Donald Trump selected J.D. Vance, an Ohio senator and author of the best-selling memoir Hillbilly Elegy, as the Republican vice presidential candidate.

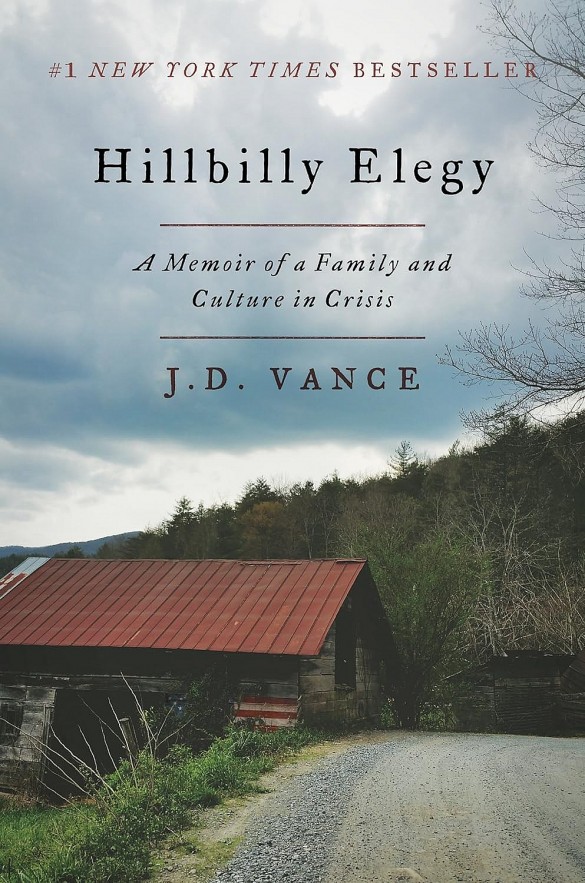

Vance, a Yale Law School graduate and investor, rose to national prominence in 2016 with his book Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. Growing up in Appalachia, working-class white people face poverty, abuse, and addiction.

Despite receiving a lot of controversy and criticism for both social and historical reasons, Vance's memoir is still very popular, reaching number one on the New York Times bestseller list, and could be adapted into a movie in November 2020.

While not well received upon release, this film adaptation received two Academy Award nominations for Best Supporting Actress and Outstanding Makeup and Hairstyling.

JD Vance: Why I don't talk about my military service

|

| J.D. Vance in the Marine Corps |

J.D Vance - 4 Year in the Marines

Vance was in the Marines for four years, from 2003 to 2007, and was a combat correspondent. In late 2005, he was sent to Iraq for six months.

Trump made it official on Monday that Vance is his choice for Vice President. In the history of the United States, President James Buchanan was a private in the Pennsylvania militia during the War of 1812. If Vance were to become president, he would be the first former Marine and only the second former enlisted veteran to hold the office. George W. Bush, who left office in 2008, was the last President to have been in the military.

Vance's 2016 book Hillbilly Elegy made him famous and started his political career. In it, he talked about how the Marine Corps changed him from an Ohio kid from a small town who didn't think much about his own responsibility into a driven young man with goals and a sense of purpose.

"The Marine Corps taught me how to live like an adult," he writes at the end.

The Pentagon gave Task & Purpose Vance's service record, which shows that he was a Combat Correspondent in the Marines for four years. He was in the Marine Corps and worked with the 2nd Marine Aircraft In Wing at Cherry Point, North Carolina. The Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal and the Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medal were two of the awards he received. These are typical of a Marine with a clean record and the same amount of time in service as Vance.

Vance tells a story from recruit training in "Hillbilly Elegy" about how he first learned the Marines' "give it your all" philosophy. After finishing a three-mile fitness test run in 25 minutes, he told the Drill Instructor how angry he was because he had never run before boot camp. The DI yelled at Recruit Vance, "If you're not throwing up, you're lazy!" "Stop being so damn lazy!"

Vance remembers, "He then told me to run back and forth between him and a tree." "He gave up just as I thought I was going to pass out." It was so hard for me to catch my breath. "That's how you should feel after every run!"

Vance writes that giving your all was a way of life in the Marines.

There are a lot of similar stories of moral and personal growth in Vance's one chapter about his time in the Marines.

“When I joined the Marine Corps, I did so in part because I wasn’t ready for adulthood,” Vance writes. “I didn’t know how to balance a checkbook, much less how to complete the financial aid forms for college. Now I knew exactly what I wanted out of my life and how to get there.”

A combat correspondent for the Marine CorpsCpl. James D. Hamel, a combat correspondent for the Marine Corps with the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing, wrote an article at Al Asad Airbase in Iraq in November 2005 about how hard the Marine Aerial Refueler Transport Squadron 252 works to keep their KC-130Js in the air. In the article on the Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, Capt. Michael S. Roberts, a pilot with VMGR-252, told Cpl. Hamel, "Without the aircrew, no one would be able to fly." "A good crew or a bad crew can make the difference between a mission that fails and one that succeeds." |

No Combat with Some Awards

In March 2004, PVT Vance was moved to Fort Meade, Maryland, to train at the Defense Information School for Public Affairs. He was also given the rank of Private First Class. In July 2004, PFC Vance was sent to Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina. He was put in charge of Public Affairs for the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing.

In August 2004, PFC Vance was sent from Cherry Point to Haiti as part of the UN Mission to Keep the Peace. Less than 100 US Marines landed in Port-au-Prince to bring order back to the country after Jean Bertrand-Aristide quit as president and fled to Africa to avoid being forced to leave by a rebel uprising. The Marines set up defenses around the airport in the capital to get ready for the arrival of French and more American troops. The Marines' job in Haiti was fivefold: to protect U.S. citizens, secure the capital, help deliver aid, return migrants who tried to escape to the U.S., and make way for a 300-person multinational security force to bring order back to Haiti. In November 2004, the US Marines were pulled out, and PFC Vance went back to the US Marine Air Station Cherry Point, NC.

On August 5, 2005, PFC Vance left Cherry Point and went to Al Assad Air Base to help with Operation Iraqi Freedom. As part of his Public Affairs job, he rotated to different forward bases controlled by US Marine Combat Forces. He went to Al Taqaddum, Al Qaim, and Al Ramadi, among others. PFC Vance was promoted to Corporal in September 2005. One of his jobs was to accompany civilian reporters into combat zones and report on the activities of forward-deployed Combat Marines.

During the Iraqi Constitutional Elections in October 2005, Cpl. Vance made sure that Iraqi poll workers were safe. During the Iraqi Parliamentary Elections in December 2005, he also kept poll workers safe. Cpl Vance went back to Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point in March 2006 and stayed there until September 2007. After four years of active duty, he was given an honorable discharge.

Among Vance's military honors are a number of awards that are common for Marines with good records.

Vance military awards include the Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medal, Sea Service Deployment Ribbon, Iraqi Campaign Medal, Global War on Terrorism Service Medal, Letter of Appreciation (5th award), Meritorious Mast Certificate of Appreciation, and various Campaign and Service Medals.

He is also not sure about getting help from other countries, especially when it comes to Ukraine. He wants people to pay attention to American problems instead.

Vance has said that he wants to speak up for "forgotten Americans." He wants to focus on issues in his own country that matter to the people who vote for him.

|

| A photo taken as Marine by J.D. Vance, who was then known as Cpl. James D. Hamel. Lieutenant Col. David Lancaster, a Houston native and executive officer of Marine Attack Squadron 223, poses in front of an AV-8B Harrier from his squadron, Jan. 1, 2006, at Al Asad, Iraq (original photo adjusted for brightness by Task & Purpose) |

Vance's second of three legal names was James D. Hamel when he was in the Marines. Vance was given the name James Donal Bowman, which comes from his real father. After his parents got a divorce, his mother changed his name to Hamel when she married him. Vance got his third name as an adult, a long time after he left the Marines. As reported by the New York Times, he and his wife changed their names to Vance when they got married. This is the name of his maternal grandparents.

At least four of his pictures from his time as a Cpl. are still online in a Pentagon archive from 2005.

As a U.S. Senator from Ohio, Vance has strong military views. He is skeptical of giving aid to Ukraine and wants the U.S. military to play a bigger role in stopping drug trafficking.

Vance wrote that as a Marine, he never fought directly, but he did go on missions with other Marines in dangerous areas, including one that made a big impression on him.

“On our particular mission, senior marines met with local school officials while the rest of us provided security or hung out with the schoolkids,” Vance writes “One very shy boy approached me and held out his hand. When I gave him a small eraser, his face briefly lit up with joy before he ran away to his family, holding his two-cent prize aloft in triumph. I have never seen such excitement on a child’s face.”

J.D. Vance: What I Learned in the Marine Corps

My final two years in the Marines flew by and were largely uneventful, though two incidents stand out, each of which speaks to the way the Marine Corps changed my perspective. The first was a moment in time in Iraq, where I was lucky to escape any real fighting but which affected me deeply nonetheless. As a public affairs marine, I would attach to different units to get a sense of their daily routine. Sometimes I’d escort civilian press, but generally I’d take photos or write short stories about individual marines or their work. Early in my deployment, I attached to a civil affairs unit to do community outreach. Civil affairs missions were typically considered more dangerous, as a small number of marines would venture into unprotected Iraqi territory to meet with locals. On our particular mission, senior marines met with local school officials while the rest of us provided security or hung out with the schoolkids, playing soccer and passing out candy and school supplies. One very shy boy approached me and held out his hand. When I gave him a small eraser, his face briefly lit up with joy before he ran away to his family, holding his two-cent prize aloft in triumph. I have never seen such excitement on a child’s face.

I don’t believe in epiphanies. I don’t believe in transformative moments, as transformation is harder than a moment. I’ve seen far too many people awash in a genuine desire to change only to lose their mettle when they realized just how difficult change actually is. But that moment, with that boy, was pretty close for me. For my entire life, I’d harbored resentment at the world. I was mad at my mother and father, mad that I rode the bus to school while other kids caught rides with friends, mad that my clothes didn’t come from Abercrombie, mad that my grandfather died, mad that we lived in a small house. That resentment didn’t vanish in an instant, but as I stood and surveyed the mass of children of a war-torn nation, their school without running water, and the overjoyed boy, I began to appreciate how lucky I was: born in the greatest country on earth, every modern convenience at my fingertips, supported by two loving hillbillies, and part of a family that, for all its quirks, loved me unconditionally. At that moment, I resolved to be the type of man who would smile when someone gave him an eraser. I haven’t quite made it there, but without that day in Iraq, I wouldn’t be trying.

|

| Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis |

The other life-altering component of my Marine Corps experience was constant. From the first day, with that scary drill instructor and a piece of cake, until the last, when I grabbed my discharge papers and sped home, the Marine Corps taught me how to live like an adult.

The Marine Corps assumes maximum ignorance from its enlisted folks. It assumes that no one taught you anything about physical fitness, personal hygiene, or personal finances. I took mandatory classes about balancing a checkbook, saving, and investing. When I came home from boot camp with my fifteen-hundred-dollar earnings deposited in a mediocre regional bank, a senior enlisted marine drove me to Navy Federal—a respected credit union—and had me open an account. When I caught strep throat and tried to tough it out, my commanding officer noticed and ordered me to the doctor.

We used to complain constantly about the biggest perceived difference between our jobs and civilian jobs: In the civilian world, your boss wasn’t able to control your life after you left work. In the Marines, my boss didn’t just make sure I did a good job, he made sure I kept my room clean, kept my hair cut, and ironed my uniforms. He sent an older marine to supervise as I shopped for my first car so that I’d end up with a practical car, like a Toyota or a Honda, not the BMW I wanted. When I nearly agreed to finance that purchase directly through the car dealership with a 21-percent-interest-rate loan, my chaperone blew a gasket and ordered me to call Navy Fed and get a second quote (it was less than half the interest). I had no idea that people did these things. Compare banks? I thought they were all the same. Shop around for a loan? I felt so lucky to even get a loan that I was ready to pull the trigger immediately. The Marine Corps demanded that I think strategically about these decisions, and then it taught me how to do so.

Just as important, the Marines changed the expectations that I had for myself. In boot camp, the thought of climbing the thirty- foot rope inspired terror; by the end of my first year, I could climb the rope using only one arm. Before I enlisted, I had never run a mile continuously. On my last physical fitness test, I ran three of them in nineteen minutes. It was in the Marine Corps where I first ordered grown men to do a job and watched them listen; where I learned that leadership depended far more on earning the respect of your subordinates than on bossing them around; where I discovered how to earn that respect; and where I saw that men and women of different social classes and races could work as a team and bond like family. It was the Marine Corps that first gave me an opportunity to truly fail, made me take that opportunity, and then, when I did fail, gave me another chance anyway. When you work in public affairs, the most senior marines serve as liaisons with the press. The press is the holy grail of Marine Corps public affairs: the biggest audience and the highest stakes. Our media officer at Cherry Point was a captain who, for reasons I never understood, quickly fell out of favor with the base’s senior brass. Though he was a captain—eight pay grades higher than I was—because of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, there was no ready replacement when he got the ax. So my boss told me that for the next nine months (until my service ended) I would be the media relations officer for one of the largest military bases on the East Coast.

By then I’d grown accustomed to the sometimes random nature of Marine Corps assignments. This was something else entirely. As a friend joked, I had a face for radio, and I wasn’t prepared for live TV interviews about happenings on base. The Marine Corps threw me to the wolves. I struggled a bit at first— allowing some photographers to take photos of a classified aircraft; speaking out of turn at a meeting with senior officers—and I got my ass chewed. My boss, Shawn Haney, explained what I needed to do to correct myself. We discussed how to build relationships with the press, how to stay on message, and how to manage my time. I got better, and when hundreds of thousands flocked to our base for a biannual air show, our media relations worked so well that I earned a commendation medal.

The experience taught me a valuable lesson: that I could do it. I could work twenty-hour days when I had to. I could speak clearly and confidently with TV cameras shoved in my face. I could stand in a room with majors, colonels, and generals and hold my own. I could do a captain’s job even when I feared I couldn’t.

For all my grandma’s efforts, for all of her “You can do anything; don’t be like those fuckers who think the deck is stacked against them” diatribes, the message had only partially set in before I enlisted. Surrounding me was another message: that I and the people like me weren’t good enough; that the reason Middletown produced zero Ivy League graduates was some genetic or character defect. I couldn’t possibly see how destructive that mentality was until I escaped it. The Marine Corps replaced it with something else, something that loathes excuses. “Giving it my all” was a catchphrase, something heard in health or gym class. When I first ran three miles, mildly impressed with my mediocre twenty-five-minute time, a terrifying senior drill instructor greeted me at the finish line: “If you’re not puking, you’re lazy! Stop being fucking lazy!” He then ordered me to sprint be- tween him and a tree repeatedly. Just as I felt I might pass out, he relented. I was heaving, barely able to catch my breath. “That’s how you should feel at the end of every run!” he yelled. In the Marines, giving it your all was a way of life.

I’m not saying ability doesn’t matter. It certainly helps. But there’s something powerful about realizing that you’ve undersold yourself—that somehow your mind confused lack of effort for inability. This is why, whenever people ask me what I’d most like to change about the white working class, I say, “The feeling that our choices don’t matter.” The Marine Corps excised that feeling like a surgeon does a tumor.

A few days after my twenty-third birthday, I hopped into the first major purchase I’d ever made—an old Honda Civic— grabbed my discharge papers, and drove one last time from Cherry Point, North Carolina, to Middletown, Ohio. During my four years in the Marines, I had seen, in Haiti, a level of poverty I never knew existed. I witnessed the fiery aftermath of an airplane crash into a residential neighborhood. I had watched Mamaw die and then gone to war a few months later. I had befriended a former crack dealer who turned out to be the hardest-working marine I knew.

When I joined the Marine Corps, I did so in part because I wasn’t ready for adulthood. I didn’t know how to balance a checkbook, much less how to complete the financial aid forms for college. Now I knew exactly what I wanted out of my life and how to get there. And in three weeks, I’d start classes at Ohio State.