Who is Zitkala-Sa – celebrated by Google doodle: Biography, Career and Personal Life

|

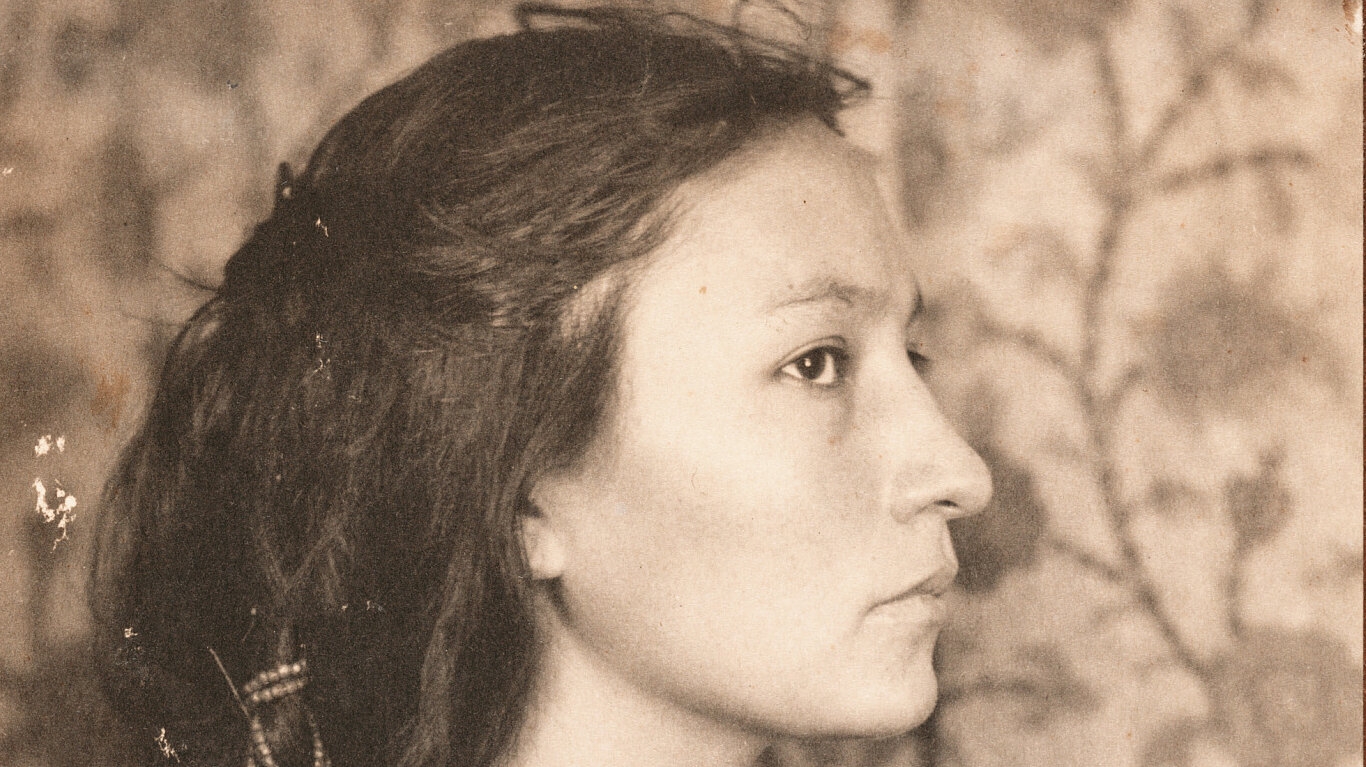

| Zitkala-Sa. Photo: fiveminutehistory |

One of the first Native American women to publish traditional stories derived from oral tribal legend was Zitkala-Sa, whose real name was Gertrude Simmons. She was born at the Yankton Sioux Agency in South Dakota, from a white father and a Dakota Indian mother. Her writing was full of imagery and emotion and frequently harangued on the white oppression of Native Americans.

Biography

Zitkala-Sa, (Lakota: “Red Bird”) birth name Gertrude Simmons, married name Gertrude Bonnin, (born February 22, 1876, Yankton Sioux Agency, South Dakota, U.S.—died January 26, 1938, Washington, D.C.), writer and reformer who strove to expand opportunities for Native Americans and to safeguard their cultures, Britannica reported.

Early Life and Education

A member of the Yankton Dakota Sioux, she was raised by her mother after her father abandoned the family. When she was eight years old, Quaker missionaries visited the Reservation, taking several of the children (including Zitkala-Ša) to Wabash, Indiana to attend White’s Indiana Manual Labor Institute. Zitkala-Ša left despite her mother’s disapproval. At this residential school, Zitkala-Ša was given the missionary name Gertrude Simmons, according to Nps.

When Zitkala-Sa was eight years old, missionaries from the White’s Manual Labor Institute in Indiana came to the Yankton reservation to recruit children for their boarding school. Zitkala-Sa’s older brother had recently returned from such a school, and her mother was hesitant to send her daughter away. Zitkala-Sa, however, was eager to go. For children who had never been off the reservation, the school sounded like a magical place. The missionaries told stories about riding trains and picking red apples in large fields. After debating the decision, Zitkala-Sa’s mother agreed to let her go. She did not want her daughter to leave and did not trust the white strangers, but she feared that the Dakota way of life was ending. There were no schools on the reservation, and she wanted her daughter to have an education.

According to her autobiography, as soon as Zitkala-Sa boarded the train, she regretted begging her mother to let her go. She was about to spend years away from everything she knew. She did not know English, and tribal languages were banned at the school. She would be forced to give up her Dakota culture for an “American” one.

Zitkala-Sa’s arrival at the school was traumatic. The children learned that everyone would get a haircut. In Dakota culture, the only people to get haircuts were cowards who had been captured by the enemy. Zitkala-Sa resisted by hiding in an empty room. When the staff of the school found her underneath a bed, they dragged her out, tied her to a chair, and cut off her braids as she cried out loud. Later in life, she wrote that the staff at the school did not care about her feelings and treated the children like “little animals.”

After a few years, the school granted Zitkala-Sa permission to visit her mother during a school break. During the visit, her mother encouraged her to abandon school and stay at home. But she later wrote that visiting homemade her sad. She returned to the school. Like many children, she may have felt that she no longer belonged on the reservation. Life at the school had changed her.

In 1895, Zitkala-Sa graduated and joined a teacher training program at Earlham College in Indiana, where she was one of the few Native American students. She then transferred to the New England Conservatory of Music, where she studied the violin. By 1900, she was teaching music and speech at the Carlisle Indian School, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, one of the most famous boarding schools in the country.

Zitkala-Sa worked at the Carlisle School for less than two years. The experience reminded her of her own traumatic education. She watched a new generation of young children arrive on trains and have their hair brutally cut. She began to question why the school required the children to give up their entire culture in exchange for an education. She saw the staff treat children cruelly, and learned that the government paid the school for every child successfully removed from a reservation. She realized the schools were designed to erase her people’s culture, Women and The American Story cited.

Marriage

In 1902 she met and married Captain Raymond Talefase Bonnin. Of mixed race, he was culturally Yankton and had one-quarter Yankton Dakota ancestry.

Soon after their marriage, Captain Bonnin was assigned to the Uintah-Ouray reservation in Utah. The couple lived and worked there with the Ute people for the next fourteen years. During this period, Zitkala-Ša gave birth to the couple's only son, Alfred Ohiya Bonnin.

By 1916, Zitkala-Sa and her husband wanted to more actively fight for the rights of Native people. They relocated to Washington, D.C., where she worked for the Society for American Indians and American Indian Magazine. In 1926, Zitkala-Sa and her husband founded the National Council of American Indians. She also organized the Indian Welfare Committee on behalf of the National General Federation of Women’s Clubs.

Literary Career

|

| Photo: nytimes |

In 1899, she took a job as a music teacher at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. From 1879 until 1918, it was the flagship Indian boarding school in the United States and used as a model for many others. In 1900, the school sent Zitkala-Ša back to the Yankton Reservation to gather more students. She was shocked to find her family home in disrepair, the extensive poverty, and that white settlers were occupying land given to the Yankton Dakota people by the federal government. She returned to Carlisle and began writing about Native American life. Her autobiographical and Lakota stories presented her people as generous and loving instead of the common racist stereotypes that portrayed Native Americans as ignorant savages. These stereotypes were being used as arguments for why Native Americans needed to be assimilated into white American society. Her writing, which was deeply critical of the boarding school system, was published in the national English magazines including Atlantic Monthly and Harper’s Monthly. In 1901, she wrote for Harper’s Monthly a piece that described the profound loss of identity felt by a student at the Carlisle Indian School. She was fired.

Afterward, she spent some time back at home on the Reservation taking care of her mother and collecting stories for her book, Old Indian Legends. She also took work at the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) office at Standing Rock Indian Reservation as a clerk. She married Captain Raymond Talefase Bonnin in 1902. They were assigned to the Uintah-Ouray Reservation in Utah, where they lived and worked for the next fourteen years. While there, they had a son, Raymond Ohiya Bonnin.

In 1910, Zitkala-Ša met William F. Hanson, a professor at Brigham Young University in Utah.[d] Together they collaborated on an opera. The Sun Dance Opera was completed in 1913. Based on the sacred Sioux ritual that the federal government had prohibited, Zitkala-Ša wrote the libretto and songs. The Sun Dance Opera was the first American Indian opera written. It is a symbol of how Zitkala-Ša lived in and bridged both her traditional Native American world and the world of white America that she was raised in.

While on the Uintah-Ouray Reservation, Zitkala-Ša joined the Society of American Indians, a group founded in 1911 with the purpose of preserving traditional Native American culture while also lobbying for full American citizenship. Beginning in 1916, Zitkala-Ša was the Society’s secretary. In this position, she corresponded with the (BIA). She became increasingly vocal in her criticism of the Bureau’s assimilationist policies and practice, reporting abuse of children when they, for example, refused to pray as Christians. Her husband Raymond was fired from the BIA office in 1916.

The family moved to Washington, DC. Zitkala-Ša continued her work with the Society of American Indians, where she was colleagues with Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin. From 1918 to 1919 Zitkala-Ša edited their journal, American Indian Magazine. She lectured across the country promoting the preservation of Native American cultural and tribal identities (though she was adamantly against the traditional use of peyote, likening it to the destructive effects of alcohol in Native communities). While being sharply critical of assimilation, she was firm in her conviction that Indigenous people in America should be American citizens, and that as citizens, they should have the vote: “In the land that was once his own – America… there was never a time more opportune than now for American to enfranchise the Redman!” As original occupants of the land, she argued, Native Americans needed to be represented in the current system of government.

The federal Indian Citizenship Act passed in 1924. It granted US citizenship rights to all Native Americans. However, this did not guarantee the vote. States retained the authority to decide who could and could not vote. In 1926, Zitkala-Ša and her husband founded the National Council of American Indians. Until her death in 1938, Zitkala-Ša served as president, fundraiser, and speaker. The Council worked to unite the tribes across the United States to gain suffrage for all Indians. She also worked with white suffrage groups and was active in the General Federation of Women’s Clubs beginning in 1921. This group worked to maintain a public voice for the concerns of diverse women. Zitkala-Ša created the Indian Welfare Committee of the Federation in 1924. That year, she ran a voter registration drive among Native Americans, encouraging those who could engage in the democratic process and support legislation that would be good for Native Americans. Published that year was a piece co-authored by Zitkala-Ša: Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians: An Orgy of Graft and Exploitation of the Five Civilized Tribes – Legalized Robbery.” This article was instrumental in getting the government to investigate the exploitation and defrauding of Native Americans by outsiders for access to oil-rich lands and in the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934.

Until her death on January 26, 1928, Zitkala-Ša continued to work for improvements in education, health care, and legal recognition of Native Americans as well as the preservation of Native American culture. She died in Washington, DC. She is buried at Arlington National Cemetery with her husband. Sharing a headstone, she is memorialized as: “His Wife / Gertrude Simmons Bonnin / Zitkala-Ša of the Sioux Indians / 1876-1936.”

What age was Zitkala-Sa when she died?Zitkala-Ša - also known as suffragist and voting rights activist Gertrude Simmons Bonnin - died in Virginia in 1938. The National Park Service in the US explains that she and her husband, Raymond Bonnin, both of the Yankton Sioux (or Dakota) Nation, chose Arlington National Cemetery as their final resting place. She was eligible for burial there as a veteran's spouse due to Raymond's US Army service in the Great War, and he later joined her. Her tombstone reads: "Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, 'Zitkala-Ša of the Sioux' 1876-1938" with a tepee carved on the back. This message was one she had spent much of her life explaining to non-Native Americans: she could be both a citizen of the US and a citizen of the Yankton Sioux Nation - she did not have to choose. |

A Legacy of Numerous Accomplishments

Gertrude Bonnin a well-known poet and writer, but also known for many other accomplishments, according to Owlcation:

- As a musician, in 1910, Bonnin helped write in collaboration with composer William F. Hanson, The Sun Dance Opera, which premiered in 1913, at Orpheus Hall, in Vernal, Utah.

- The Broadway Theatre ran The Sun Dance Opera in 1938, but it was unfortunate that the billboard only featured William F. Hanson as the only composer.

- As a member of the Society of American Indians, she dedicated her time to fighting Native American rights to gain full citizenship.

- In 1916, she became an outspoken voice for the Society of American Indians as the group’s elected Secretary she pushed for an investigation into corrupt practices by the Bureau of Indian Affairs against the abuse of Native American children.

- In 1921, Bonnin joined the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, an organization that promoted women’s rights.

- Recognized in the Scientific community, by giving her an honorary title, naming a crater after the Native American authoress on the planet Venus.

- Named a 1999 Honoree by the National Women’s History Project.

- Upon her death, Gertrude Bonnin’s burial began in Washington DC at the prestigious Arlington National Cemetery.

Zitkala-Sa's most famous quotes

|

| Photo: quotesgram |

In 1901 Zitkala-Sa's Old Indian Legends - passed down by oral storytellers of her Sioux tribe - was published.

American Indian Stories was published in 1921.

In the book the Sioux Indian and activist writes poignantly of her childhood summer days when her mother built her fire in the "shadow of our wigwam", and she was entranced by the telling of legends, punctured by the "distant howling of a pack of wolves or the hooting of an owl".

The author is known for many beautiful and thought-provoking quotes including:

- "There is no great; there is no small; in the mind that causeth all."

- "Let us not look for good or justice: then we shall not be disappointed!"

- "A wee child toddling in a wonder world, I prefer to their dogma my excursions into the natural gardens where the voice of the Great Spirit is heard in the twittering of birds, the rippling of mighty waters, and the sweet breathing of flowers. If this is Paganism, then at present, at least, I am a Pagan."

- “Few there are who have paused to question whether real-life or long-lasting death lies beneath this semblance of civilization.”

- “I was not wholly conscious of myself but was more keenly alive to the fire within. It was as if I were the activity, and my hands and feet were only experiments for my spirit to work upon."

Why is she being celebrated as today's Google Doodle?

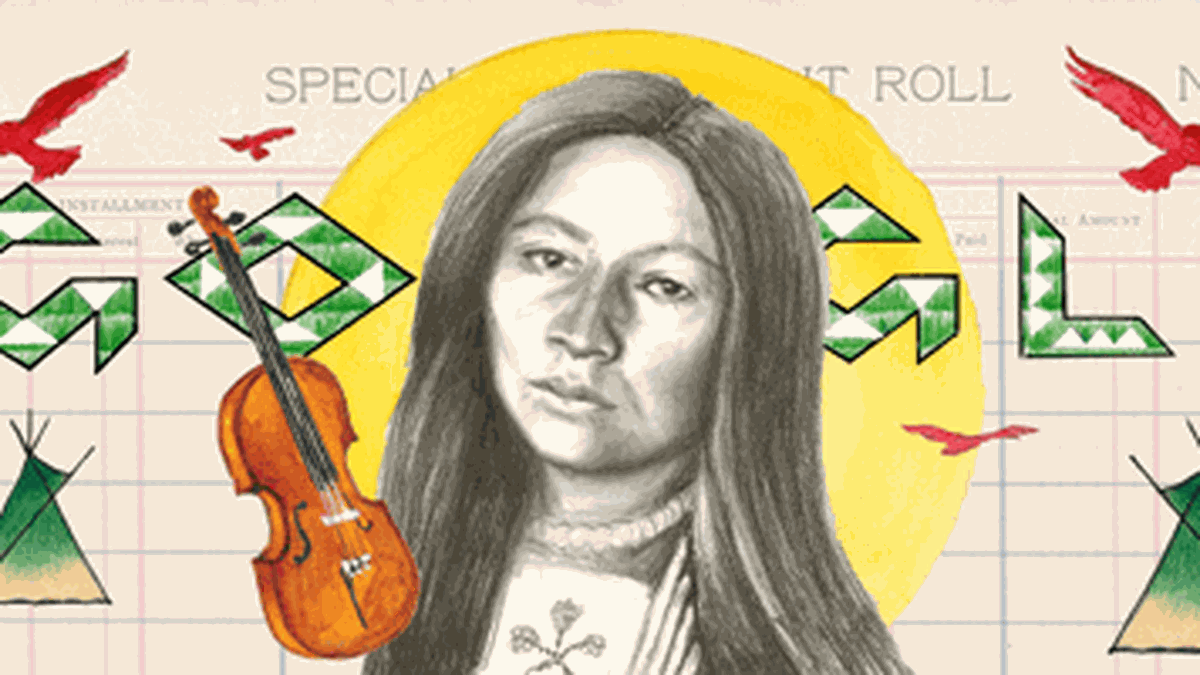

|

| Photo: dakotanewsnow |

On this day (February 22) in 1876, Zitkala-Ša (Lakota for “Red Bird”) - also known as Gertrude Simmons - was born on the Yankton Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

While attending the White’s Indiana Manual Labor Institute, a missionary boarding school, her hair was cut against her will, and she was forbidden to speak her Lakota language.

The then eight-year-old was also forced to practice a religion she didn’t believe in. She went on to attend graduate college, study and perform violin, teach, and write about the American Indian experience, including her autobiography, writes the United Nations Foundation. Zitkala-Ša integrated her traditional heritage with modern ideas and was a vocal supporter of native rights and citizenship and women’s suffrage.

She was elected as one of the leaders of the Society of American Indians, a political advocacy group. Zitkala-Ša supported American Indians’ dual citizenship in native tribes and the US, crisscrossing the country to urge white women, newly able to vote, to support Indian rights.

Thanks in part to Zitkala-Ša’s grassroots organizing, the Indian Citizenship Act was enacted in 1924.

She was "a woman who lived resiliently during a time when the Indigenous people of the US were not considered real people by the American government, let alone citizens", says Google.

Zitkala-Ša devoted her life to the protection and celebration of her Indigenous heritage through the arts and activism.

Her special Google Doodle was created by Chris Pappan, an American Indian guest artist of Osage, Kaw, Cheyenne River Sioux, and European heritage, according to The Sun.

Google DoodleIn 1998, the search engine founders Larry and Sergey drew a stick figure behind the second 'o' of Google as a message that they were out of an office at the Burning Man festival, and with that, Google Doodles were born. The company decided that they should decorate the logo to mark cultural moments and it soon became clear that users really enjoyed the change to the Google homepage. In that same year, a turkey was added to Thanksgiving and two pumpkins appeared as the 'o's for Halloween the following year. Now, there is a full team of doodlers, illustrators, graphic designers, animators, and classically trained artists who help create what you see on those days. |

WandaVision: Who is Kathryn Hahn (Agnes) - the last Villain? WandaVision: Who is Kathryn Hahn (Agnes) - the last Villain? WandaVision has revealed a new extremely powerful character, behind many bizarre events in many episodes: veteran witch Agatha Harkness. Who is Actress Kathryn Hahn - ... |

Who is Jessica Watkins - Oath Keepers Leader: Bio, Capitol Riot Arrest, Court Fillings Who is Jessica Watkins - Oath Keepers Leader: Bio, Capitol Riot Arrest, Court Fillings Jessica Watkins of the far-right militia Oath Keepers was arrested because of the participation in the Capitol riot on January 6. Check out for more ... |

Who is Malcolm X: Biography, New Evidence in Assassination and Personal Profile Who is Malcolm X: Biography, New Evidence in Assassination and Personal Profile Who is Malcolm X: Biography, Personal Profile and New Evidence in Assassination points to possible conspiracy after fifty-six years. |

Who is Nikki Haley: Biography, Husband&Children, Career and Personal Profile&Life Who is Nikki Haley: Biography, Husband&Children, Career and Personal Profile&Life Who is Nikki Haley: Biography, Husband & Children, Political Career, Personal Profile & Life and Facts about her. |