Top 10 Most Famous Classic Poems In The World

|

| What Are The Best and Most Famous Classic Poems? |

| Table Content |

A poem is generally not described as "classic" until several decades have passed since it was originally penned and released to the public. Adequate time must have elapsed for the poem to have demonstrated its staying power. If high school seniors are still assigned to analyze the poem 50 to 100 years after the poet has passed away, it is a good sign that it is a classic poem.

In the past, the addition of non-Western poetry to the classic poetry canon has been impeded by language and cultural differences. Thankfully, modern academics have taken care to include a diverse assortment of poems in the classic category. Long-standing classic poems survive the effects of time and cultural shifts. Anthologies of classic poetry now contain representative writings from all corners of the globe, in translations of many languages, and from a variety of eras of human history. In fact, some famous Chinese poems dedicated to cultural deities date from 1000 BC.

We have looked through websites, social media and own interests on classic poems, which helped us come up with this list of top 10 the best and most famous classic poems.

List of top 10 best and most famous classic poems in the world

10. “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou

9. “We Wear the Mask” by Paul Laurence Dunbar

8. “The Builders” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

7. “On the Stork Tower” by Wang Zhihuan

6. “Horatius” by Thomas Babington

5. “Mending Wall” by Robert Frost

4. “O Captain! My Captain!” by Walt Whitman

3. “Invictus” by William Ernest Henley

2. “She Walks in Beauty” by Lord Byron

1. “Ulysses” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

***

What Are The Best and Most Famous Classic Poems Around The World?

10. “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou

Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don't you take it awful hard

’Cause I laugh like I've got gold mines

Diggin’ in my own backyard.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.

This stirring poem is packed full of figurative language. It functions as a sort of secular hymn to the oppressed and abused. The message is loud and clear—no matter the cruelty, regardless of method and circumstance, the victim will rise up, the slave will overcome adversity. (It's little wonder that Nelson Mandela read this poem at his inauguration in 1994 after spending 27 years in prison.)

Although written with black slavery and civil rights issues in mind, "Still I Rise" is universal in its appeal. Any innocent individual, any minority, or any nation subject to oppression or abuse can understand its underlying theme—don't give in to torture, bullying, humiliation, and injustice.

This poem includes 43 lines in total, made up of seven quatrains and two end stanzas which help reinforce the theme of individual hope, with the phrase "I rise" being repeated like a mantra, according to Owlcation.

If this poem were a sculpture, it would have a granite plinth to stand on. The natural imagery is far-reaching and the voice is loud. In this poem there are moons and suns, tides and black oceans. There is a clear daybreak and ancestral gifts, all joining together in a crescendo of hope.

Owlcation also wrote, "Stanza six brings the oppressive issue to a climax. Three lines begin with "You," the speaker, choosing particularly active verbs—"shoot," "cut," and "kill"—to emphasize the aggression. But this aggression comes to no avail, for the oppressed will still rise, this time like air, an element which you cannot shoot, cut, or kill."

All in all, this is an inspirational poem with a powerful repetitive energy, a universal message, and a clear, positive pulse throughout.

9. “We Wear the Mask” by Paul Laurence Dunbar

|

| Photo: Pinterest |

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,—

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

In the first stanza of this piece, the speaker begins by utilizing the refrain. It is also the line that later became the title of the poem. He is using the word “We” to allow the reader to include themselves in the text. All people are among those who “wear mask[s].”

That being said, Dunbar is well-known as a pioneer of the Harlem Renaissance. This likely means that the “We” is geared more towards black Americans. The type of masks that “We” wear include “grins and lies.” One readily puts on another face for any particular situation. Lies, for when one needs to pretend to be something they aren’t, and grins for getting by in uncomfortable situations, according to the analysis of Poem Analysis.

These masks hide someone’s real “cheeks and…eyes.” It puts one at distance from their surroundings. The speaker goes on to attribute the masks to be the product of “human guile.” In this context, guile refers to general deceitfulness. This is an overwhelming human trait. It is nearly impossible to get through modern life completely as one’s self.

The fourth stanza of this piece is a quatrain, meaning it contains four lines. These lines begin with the speaker asking a rhetorical question. He does not expect to receive an answer. This does not mean the question lacks importance. It is posed to make one consider the state of the world and perhaps further the question themselves.

In the final line, the speaker brings back the title of the poem, “We wear the mask.” This line is used as a reminder that not only are the troubles of the world obscured, they are purposefully hidden, at least to some extent, cited by Poem Analysis.

The final stanza of this piece contains six lines. It begins with the speaker increasing the already dark nature of the piece. He explains how “We smile” but no matter what the “cries” come out from “tortured souls.” They “arise” from behind the mask and into the real, knowable world.

8. “The Builders” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

All are architects of Fate,

Working in these walls of Time;

Some with massive deeds and great,

Some with ornaments of rhyme.

Nothing useless is, or low;

Each thing in its place is best;

And what seems but idle show

Strengthens and supports the rest.

For the structure that we raise,

Time is with materials filled;

Our to-days and yesterdays

Are the blocks with which we build.

Truly shape and fashion these;

Leave no yawning gaps between;

Think not, because no man sees,

Such things will remain unseen.

In the elder days of Art,

Builders wrought with greatest care

Each minute and unseen part;

For the Gods see everywhere.

Let us do our work as well,

Both the unseen and the seen;

Make the house, where Gods may dwell,

Beautiful, entire, and clean.

Else our lives are incomplete,

Standing in these walls of Time,

Broken stairways, where the feet

Stumble as they seek to climb.

Build to-day, then, strong and sure,

With a firm and ample base;

And ascending and secure

Shall to-morrow find its place.

Thus alone can we attain

To those turrets, where the eye

Sees the world as one vast plain,

And one boundless reach of sky.

In the first stanza of this piece the speaker begins by stating that all people, no matter who they are or where they come from, are “architects of Fate.” When he refers to “All,” he is truly speaking of everyone who has ever lived, according to Poem Analysis.

The speaker has a very optimistic view of the world. He sees all inhabitants of earth as having contributed to the “walls of Time.” Every person has an impact of one size or another. Some were simply “ornaments” while others were “massive deeds.”

In the second stanza the speaker emphasizes his position on the importance of human contributions by stating that “Nothing” one does is “useless” or “low.” All things have their “place” where they belong. No matter what one person might think of another, their contributions do matter, which was analysed by Poem Analysis.

In the third quatrain of this piece begins by saying that the “structure” made by human beings is slowly being filled over the years. It is growing larger and larger and becoming “filled” with the “materials” humankind has contributed to history.

The fourth stanza describes the process of “building” up “Time” and crafting the future. Due to the fact that there are so many contributors to this process there cannot be any “yawning gaps between” or within history. It should be, the speaker says, “Truly shape[d] and fashion[ed].”

Although all inhabitants of the planet has participated in this act, no single person sees the whole picture. An overarching image of eternity is not for “man” to see, it is something to which God is only privy.

Top 10 Best And Most Famous Modern Poems Top 10 Best And Most Famous Modern Poems What are the best and most famous modern poems? Let's find out in the list below! |

7. “On the Stork Tower” by Wang Zhihuan

白日依山尽,

bái rì yī shān jǐn,

The white sun sets behind the mountains,

黄河入海流。

huáng hé rù hǎi liú。

and the Yellow River flows into the sea.

欲穷千里目,

yù qióng qiān lǐ mù,

To see a thousand mile view,

更上一层楼。

gèng shàng yì céng lóu。

go up another floor.

On The Stork Tower was composed by Wang Zhihuan (王之涣) to describe what the poet sees and feels about when he ascends the Stork Tower, according to analysis by Happy School Online website.

In the first two lines, he shifts his eyes from the sunset beyond the mountains to the Yellow River, which flows out of sight eastwards towards the sea. Then, he writes the famous lines “欲穷千里目,更上一层楼。(To see a thousand mile view, go up another floor.)” which blends landscape, emotion and philosophical thinking in the short verse. The last line, “更上一层楼”, is now a general idiom for taking things up a level, a bit like the colloquial “Cheer Up!” or “Add Oil!”.

To help better understand the poem, here to supplement and explain some key vocabularies:

• “鹳雀楼 (guàn què lóu)” is a tower in Shanxi province, with three floors, situated between mountains and the Yellow River.

• “穷 (qióng)” in the third line refers to “尽 (jǐn) ” which means “furthest”.

6. “Horatius” by Thomas Babington

|

| Photo: Tumblr |

LARS Porsena of Clusium

By the Nine Gods he swore

That the great house of Tarquin

Should suffer wrong no more.

By the Nine Gods he swore it,

And named a trysting day,

And bade his messengers ride forth,

East and west and south and north,

To summon his array.

II

East and west and south and north

The messengers ride fast,

And tower and town and cottage

Have heard the trumpet’s blast.

Shame on the false Etruscan

Who lingers in his home,

When Porsena of Clusium

Is on the march for Rome.

III

The horsemen and the footmen

Are pouring in amain

From many a stately market-place;

From many a fruitful plain;

From many a lonely hamlet,

Which, hid by beech and pine,

Like an eagle’s nest, hangs on the crest

Of purple Apennine;

IV

From lordly Volaterræ,

Where scowls the far-famed hold

Piled by the hands of giants

For godlike kings of old;

From seagirt Populonia,

Whose sentinels descry

Sardinia’s snowy mountain-tops

Fringing the southern sky;

V

From the proud mart of Pisæ,

Queen of the western waves,

Where ride Massilia’s triremes

Heavy with fair-haired slaves;

From where sweet Clanis wanders

Through corn and vines and flowers;

From where Cortona lifts to heaven

Her diadem of towers.

VI

Tall are the oaks whose acorns

Drop in dark Auser’s rill;

Fat are the stags that champ the boughs

Of the Ciminian hill;

Beyond all streams Clitumnus

Is to the herdsman dear;

Best of all pools the fowler loves

The great Volsinian mere.

VII

But now no stroke of woodman

Is heard by Auser’s rill;

No hunter tracks the stag’s green path

Up the Ciminian hill;

Unwatched along Clitumnus

Grazes the milk-white steer;

Unharmed the water fowl may dip

In the Volsinian mere.

VIII

The harvests of Arretium,

This year, old men shall reap;

This year, young boys in Umbro

Shall plunge the struggling sheep;

And in the vats of Luna,

This year, the must shall foam

Round the white feet of laughing girls

Whose sires have marched to Rome.

IX

There be thirty chosen prophets,

The wisest of the land,

Who always by Lars Porsena

Both morn and evening stand:

Evening and morn the Thirty

Have turned the verse o’er,

Traced from the right on linen white

By mighty seers of yore.

X

And with one voice the Thirty

Have their glad answer given:

‘Go forth, go forth, Lars Porsena;

Go forth, beloved of Heaven;

Go, and return in glory

To Clusium’s royal dome;

And hang round Nurscia’s altars

The golden shields of Rome.’

XI

And now hath every city

Sent up her tale of men;

The foot are fourscore thousand,

The horse are thousands ten.

Before the gates of Sutrium

Is met the great array.

A proud man was Lars Porsena

Upon the trysting day.

XII

For all the Etruscan armies

Were ranged beneath his eye,

And many a banished Roman,

And many a stout ally;

And with a mighty following

To join the muster came

The Tusculan Mamilius,

Prince of the Latian name.

XIII

But by the yellow Tiber

Was tumult and affright:

From all the spacious champaign

To Rome men took their flight.

A mile around the city,

The throng stopped up the ways;

A fearful sight it was to see

Through two long nights and days.

XIV

For aged folks on crutches,

And women great with child,

And mothers sobbing over babes

That clung to them and smiled,

And sick men borne in litters

High on the necks of slaves,

And troops of sun-burned husbandmen

With reaping-hooks and staves,

XV

And droves of mules and asses

Laden with skins of wine,

And endless flocks of goats and sheep,

And endless herds of kine,

And endless trains of waggons

That creaked beneath the weight

Of corn-sacks and of household goods,

Choked every roaring gate.

XVI

Now, from the rock Tarpeian,

Could the wan burghers spy

The line of blazing villages

Red in the midnight sky.

The Fathers of the City,

They sat all night and day,

For every hour some horseman came

With tidings of dismay.

XVII

To eastward and to westward

Have spread the Tuscan bands;

Nor house, nor fence, nor dovecote

In Crustumerium stands.

Verbenna down to Ostia

Hath wasted all the plain;

Astur hath stormed Janiculum,

And the stout guards are slain.

XVIII

I wis, in all the Senate,

There was no heart so bold,

But sore it ached, and fast it beat,

When that ill news was told.

Forthwith up rose the Consul,

Up rose the Fathers all;

In haste they girded up their gowns,

And hied them to the wall.

XIX

They held a council standing,

Before the River-Gate;

Short time was there, ye well may guess,

For musing or debate.

Out spake the Consul roundly:

‘The bridge must straight go down;

For, since Janiculum is lost,

Nought else can save the town.’

XX

Just then a scout came flying,

All wild with haste and fear:

‘To arms! to arms! Sir Consul:

Lars Porsena is here.’

On the lows hills to westward

The Consul fixed his eye,

And saw the swarthy storm of dust

Rise fast along the sky.

XXI

And nearer fast and nearer

Doth the red whirlwind come;

And louder still and still more loud,

From underneath that rolling cloud,

Is heard the trumpet’s war-note proud,

The trampling, and the hum.

And plainly and more plainly

Now through the gloom appears,

Far to left and far to right,

In broken gleams of dark-blue light,

The long array of helmets bright,

The long array of spears.

XXII

And plainly and more plainly,

Above that glimmering line,

Now might ye see the banners

Of twelve fair cities shine;

But the banner of proud Clusium

Was highest of them all,

The terror of the Umbrian,

The terror of the Gaul.

XXIII

And plainly and more plainly

Now might the burghers know,

By port and vest, by horse and crest,

Each warlike Lucumo.

There Cilnius of Arretium

On his fleet roan was seen;

And Astur of the four-fold shield,

Girt with the brand none else may wield,

Tolumnius with the belt of gold,

And dark Verbenna from the hold

By reedy Thrasymene.

XXIV

Fast by the royal standard,

O’erlooking all the war,

Lars Porsena of Clusium

Sat in his ivory car.

By the right wheel rode Mamilius,

Prince of the Latian name;

And by the left false Sextus,

That wrought the deed of shame.

XXV

But when the face of Sextus

Was seen among the foes,

A yell that rent the firmament

From all the town arose.

On the house-tops was no woman

But spat towards him and hissed,

No child but screamed out curses,

And shook its little fist.

XXVI

But the Consul’s brow was sad,

And the Consul’s speech was low,

And darkly looked he at the wall,

And darkly at the foe.

‘Their van will be upon us

Before the bridge goes down;

And if they once may win the bridge,

What hope to save the town?’

XXVII

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the gate:

‘To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his Gods,

XXVIII

‘And for the tender mother

Who dandled him to rest,

And for the wife who nurses

His baby at her breast,

And for the holy maidens

Who feed the eternal flame,

To save them from false Sextus

That wrought the deed of shame?

XXIX

‘Hew down the bridge, Sir Consul,

With all the speed ye may;

I, with two more to help me,

Will hold the foe in play.

In yon strait path a thousand

May well be stopped by three.

Now who will stand on either hand,

And keep the bridge with me?’

XXX

Then out spake Spurius Lartius;

A Ramnian proud was he:

‘Lo, I will stand at thy right hand,

And keep the bridge with thee.’

And out spake strong Herminius;

Of Titian blood was he:

‘I will abide on thy left side,

And keep the bridge with thee.’

XXXI

‘Horatius,’ quoth the Consul,

‘As thou sayest, so let it be.’

And straight against that great array

Forth went the dauntless Three.

For Romans in Rome’s quarrel

Spared neither land nor gold,

Nor son nor wife, nor limb nor life,

In the brave days of old.

XXXII

Then none was for a party;

Then all were for the state;

Then the great man helped the poor,

And the poor man loved the great:

Then lands were fairly portioned;

Then spoils were fairly sold:

The Romans were like brothers

In the brave days of old.

XXXIII

Now Roman is to Roman

More hateful than a foe,

And the Tribunes beard the high,

And the Fathers grind the low.

As we wax hot in faction,

In battle we wax cold:

Wherefore men fight not as they fought

In the brave days of old.

XXXIV

Now while the Three were tightening

Their harnesses on their backs,

The Consul was the foremost man

To take in hand an axe:

And Fathers mixed with Commons

Seized hatchet, bar, and crow,

And smote upon the planks above,

And loosed the props below.

XXXV

Meanwhile the Tuscan army,

Right glorious to behold,

Come flashing back the noonday light,

Rank behind rank, like surges bright

Of a broad sea of gold.

Four hundred trumpets sounded

A peal of warlike glee,

As that great host, with measured tread,

And spears advanced, and ensigns spread,

Rolled slowly towards the bridge’s head,

Where stood the dauntless Three.

XXXVI

The Three stood calm and silent,

And looked upon the foes,

And a great shout of laughter

From all the vanguard rose:

And forth three chiefs came spurring

Before that deep array;

To earth they sprang, their swords they drew,

And lifted high their shields, and flew

To win the narrow way;

XXXVII

Aunus from green Tifernum,

Lord of the Hill of Vines;

And Seius, whose eight hundred slaves

Sicken in Ilva’s mines;

And Picus, long to Clusium

Vassal in peace and war,

Who led to fight his Umbrian powers

From that grey crag where, girt with towers,

The fortress of Nequinum lowers

O’er the pale waves of Nar.

XXXVIII

Stout Lartius hurled down Aunus

Into the stream beneath;

Herminius struck at Seius,

And clove him to the teeth;

At Picus brave Horatius

Darted one fiery thrust;

And the proud Umbrian’s gilded arms

Clashed in the bloody dust.

XXXIX

Then Ocnus of Falerii

Rushed on the Roman Three;

And Lausulus of Urgo,

The rover of the sea;

And Aruns of Volsinium,

Who slew the great wild boar,

The great wild boar that had his den

Amidst the reeds of Cosa’s fen,

And wasted fields, and slaughtered men,

Along Albinia’s shore.

XL

Herminius smote down Aruns:

Lartius laid Ocnus low:

Right to the heart of Lausulus

Horatius sent a blow.

‘Lie there,’ he cried, ‘fell pirate!

No more, aghast and pale,

From Ostia’s walls the crowd shall mark

The track of thy destroying bark.

No more Campania’s hinds shall fly

To woods and caverns when they spy

Thy thrice accursed sail.’

XLI

But now no sound of laughter

Was heard among the foes.

A wild and wrathful clamour

From all the vanguard rose.

Six spears’ lengths from the entrance

Halted that deep array,

And for a space no man came forth

To win the narrow way.

XLII

But hark! the cry is Astur:

And lo! the ranks divide;

And the great Lord of Luna

Comes with his stately stride.

Upon his ample shoulders

Clangs loud the four-fold shield,

And in his hand he shakes the brand

Which none but he can wield.

XLIII

He smiled on those bold Romans

A smile serene and high;

He eyed the flinching Tuscans,

And scorn was in his eye.

Quoth he, ‘The she-wolf’s litter

Stand savagely at bay:

But will ye dare to follow,

If Astur clears the way?’

XLIV

Then, whirling up his broadsword

With both hands to the heights

He rushed against Horatius,

And smote with all his might,

With shield and blade Horatius

Right deftly turned the blow.

The blow, though turned, came yet too nigh;

It missed his helm, but gashed his thigh:

The Tuscans raised a joyful cry

To see the red blood flow.

XLV

He reeled, and on Herminius

He leaned one breathing-space;

Then, like a wild cat mad with wounds

Sprang right at Astur’s face.

Through teeth, and skull, and helmet

So fierce a thrust he sped,

The good sword stood a hand-breadth out

Behind the Tuscan’s head.

XLVI

And the great Lord of Luna

Fell at that deadly stroke,

As falls on Mount Alvernus

A thunder smitten oak.

Far o’er the crashing forest

The giant’s arms lie spread;

And the pale augurs, muttering low,

Gaze on the blasted head.

XLVII

On Astur’s throat Horatius

Right firmly pressed his heel,

And thrice and four times tugged amain,

Ere he wrenched out the steel.

‘And see,’ he cried, ‘the welcome,

Fair guests, that waits you here!

What noble Lucumo comes next

To taste our Roman cheer?’

XLVIII

But at his haughty challenge

A sullen murmur ran,

Mingled of wrath, and shame, and dread,

Along that glittering van.

There lacked not men of prowess,

Nor men of lordly race;

For all Etruria’s noblest

Were round the fatal place.

XLIX

But all Etruria’s noblest

Felt their hearts sink to see

On the earth the bloody corpses,

In the path the dauntless Three:

And, from the ghastly entrance

Where those bold Romans stood,

All shrank, like boys who unaware,

Ranging the woods to start a hare,

Come to the mouth of the dark lair

Where, growling low, a fierce old bear

Lies amidst bones and blood.

L

Was none who would be foremost

To lead such dire attack:

But those behind cried ‘Forward!’

And those before cried ‘Back!’

And backward now and forward

Wavers the deep array;

And on the tossing sea of steel,

To and fro the standards reel;

And the victorious trumpet-peal

Dies fitfully away.

LI

Yet one man for one moment

Strode out before the croud;

Well known was he to all the Three,

And they gave gim greeting loud.

‘Now welcome, welcome, Sextus!

Now welcome to thy home!

Why dost thou stay, and turn away?

Here lies the road to Rome.’

LII

Thrice looked he at the city;

Thrice looked he at the dead;

And thrice came on in fury,

And thrice turned back in dread:

And, white with fear and hatred,

Scowled at the narrow way

Where, wallowing in a pool of blood,

The bravest Tuscans lay.

LIII

But meanwhile axe and lever

Have manfully been plied;

And now the bridge hangs tottering

Above the boiling tide.

‘Come back, come back, Horatius!’

Loud cried the Fathers all.

‘Back, Lartius! back, Herminius!

Back, ere the ruin fall!’

LIV

Back darted Spurius Lartius;

Herminius darted back:

And, as they passed, beneath their feet

They felt the timbers crack.

But when they turned their faces,

And on the farther shore

Saw brave Horatius stand alone,

They would have crossed once more.

LV

But with a crash like thunder

Fell every loosened beam,

And, like a dam, the mighty wreck

Lay right athwart the stream:

And a long shout of triumph

Rose from the walls of Rome,

As to the highest turret-tops

Was splashed the yellow foam.

LVI

And, like a horse unbroken

When first he feels the rein,

The furious river struggled hard,

And tossed his tawny mane,

And burst the curb and bounded,

Rejoicing to be free,

And whirling down, in fierce career,

Battlement, and plank, and pier,

Rushed headlong to the sea.

LVII

Alone stood brave Horatius,

But constant still in mind;

Thrice thirty thousand foes before,

And the broad flood behind.

‘Down with him!’ cried false Sextus,

With a smile on his pale face.

‘Now yield thee,’ cried Lars Porsena,

‘Now yield thee to our grace!’

LVIII

Round turned he, as not deigning

Those craven ranks to see;

Nought spake he to Lars Porsena,

To Sextus nought spake he;

But he saw on Palatins

The white porch of his home;

And he spake to the noble river

That rolls by the towers of Rome.

LIX

‘Oh, Tiber! father Tiber!

To whom the Romans pray,

A Roman’s life, a Roman’s arms,

Take thou in charge this day!’

So he spake, and speaking sheathed

The good sword by his side,

And with his harness on his back,

Plunged headlong in the tide.

LX

No sound of joy or sorrow

Was heard from either bank;

But friends and foes in dumb surprise,

With parted lips and straining eyes,

Stood gazing where he sank;

And when above the surges

They saw his crest appear,

All Rome sent forth a rapturous cry,

And even the ranks of Tuscany

Could scarce forbear to cheer.

LXI

But fiercely ran the current,

Swollen high by months of rain:

And fast his blood was flowing;

And he was sore in pain,

And heavy with his armour,

And spent with changing blows:

And oft they thought him sinking,

But still again he rose.

LXII

Never, I ween, did swimmer,

In such an evil case,

Struggle through such a raging flood

Safe to the landing place.

But his limbs were borne up bravely

By the brave heart within,

And our good father Tiber

Bare bravely up his chin.

LXIII

‘Curse on him!’ quoth false Sextus;

‘Will not the villain drown?

But for this stay, ere close of day

We should have sacked the town!’

‘Heaven help him!’ quoth Lars Porsena,

‘And bring him safe to shore;

For such a gallant feat of arms

Was never seen before.’

LXIV

And now he feels the bottom;

Now on dry earth he stands;

Now round him throng the Fathers;

To press his gory hands;

And now, with shouts and clapping,

And noise of weeping loud,

He enters through the River-Gate,

Borne by the joyous crowd.

LXV

They gave him of the corn-land,

That was of public right,

As much as two strong oxen

Could plough from morn till night;

And they made a molten image,

And set it up on high,

And there it stands unto this day

To witness if I lie.

LXVI

It stands in the Comitium,

Plain for all folk to see;

Horatius in his harness,

halting upon one knee:

And underneath is written,

In letters all of gold,

How valiantly he kept the bridge

In the brave days of old.

LXVII

And still his name sounds stirring

Unto the men of Rome,

As the trumpet-blast that cries to them

To charge the Volscian home;

And wives still pray to Juno

For boys with hearts as bold

As his who kept the bridge so well

In the brave days of old.

LXVIII

And in the nights of winter,

When the cold north winds blow,

And the long howling of the wolves

Is heard amidst the snow;

When round the lonely cottage

Roars loud the tempest’s din,

And the good logs of Algidus

Roar louder yet within;

LXIX

When the oldest cask is opened,

And the largest lamp is lit;

When the chestnuts glow in the embers,

And the kid turns on the spit;

When young and old in circle

Around the firebrands close;

When the girls are weaving baskets,

And the lads are shaping bows;

LXX

When the goodman mends his armour,

And trims his helmet’s plume;

When the goodwife’s shuttle merrily

Goes flashing through the loom;

With weeping and with laughter

Still is the story told,

How well Horatius kept the bridge

In the brave days of old.

The poet Thomas Babington McAulay is also known as a politician, essayist, and historian. Born in England in 1800, he wrote one of his first poems at the age of eight called "The Battle of Cheviot." Macaulay went on to college where he began to have his essays published prior to a career in politics. He was best known for his work in History of England covering the period 1688–1702. Macaulay died in 1859 in London, according to analysis by ThoughtCo.

The story of Horatius is described in Plutarch's "Life of Publicola." In the early 6th century BCE, Lars Porsena was the most powerful king in Etruscan Italy, who Tarquinius Superbus asked to help him take back Rome. Porsena sent a message to Rome saying they should receive Tarquin as their king, and when the Romans refused, he declared war on them. Publicola was the consul of Rome, and he and Lucretius defended Rome until they fell in battle.

Horatius Cocles ("Cyclops," so named because he had lost one of his eyes in the wars) was the keeper of the Gate of Rome. He stood in front of the bridge and held off the Etruscans until the Romans could put the bridge out of commission. Once that was accomplished, Horatius, wounded by a spear to his buttocks and in full armor, dove into the water and swam back to Rome, cited by ThoughtCo.

Horatius was forced to retire as a result of his injuries and, after a protracted siege of the city, Lars Porsena captured Rome, but without sacking it. Tarquinius Superbus was to be the last of the kings of Rome.

5. “Mending Wall” by Robert Frost

Something there is that doesn't love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun;

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

‘Stay where you are until our backs are turned!’

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of out-door game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn't it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I'd ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn't love a wall,

That wants it down.’ I could say ‘Elves’ to him,

But it's not elves exactly, and I'd rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father's saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

‘Mending Wall’ principally analyses the nature of human relationships. When you read ‘Mending Wall’ it feels like peeling off an onion. The reader analyses, philosophizes and dives deep to search for a definite conclusion that he is unable to find. Yet the quest is more thrilling and rewarding as compared to the Holy Grail itself. The reader understands life in a new way and challenges all definitions, according to the analysis of Poem Analysis.

At the very outset, the poem takes you to the nature of things. Therefore, the narrator says something does exist in the nature that does not want a wall. He says man makes many walls, but they all get damaged and destroyed either by nature or by the hunters who search for rabbits for their hungry dogs. Hence, as soon as the spring season starts, he (narrator), with his neighbor, sets out to repair the wall that keeps their properties separated. Though the narrator comes together with his neighbor to repair the wall, he regards it an act of stupidity. He believes that in fact both of them don’t need a wall. He asks why should there be a wall, when his neighbor has only pine trees and he has apples.

How could his apple trees go across the border and eat his neighbor’s pine cones. Moreover there is no chance of offending one and another as they don’t also have any cows at their homes. While the narrator tries to make his neighbor understand that they don’t need a wall, his neighbor is a stone-headed savage, who only believes in his father’s age-old saying that, “Good fences make good neighbors.”

Top 10 Best and Greatest Poems In English Language Of All Time Top 10 Best and Greatest Poems In English Language Of All Time Poetry can be meaningful, rhythmic and it has a certain beauty to it. Find the top 10 best and greatest poems in English language of ... |

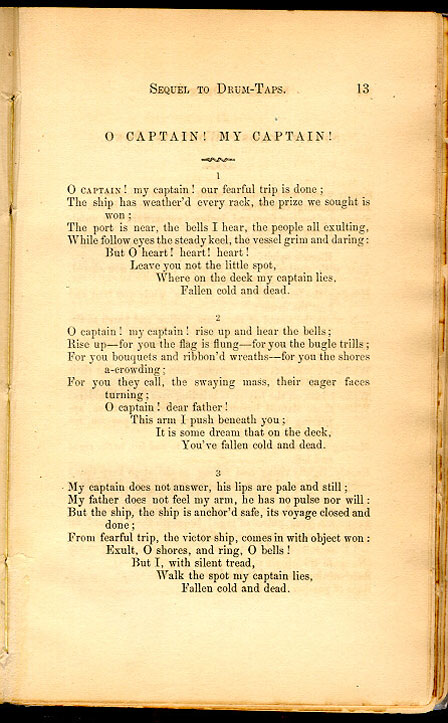

4. “O Captain! My Captain!” by Walt Whitman

|

| Photo: The Walt Whitman Archive |

But O heart! heart! heart!

O the bleeding drops of red,

Where on the deck my Captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

O Captain! my Captain! rise up and hear the bells;

Rise up—for you the flag is flung—for you the bugle trills;

For you bouquets and ribbon'd wreaths—for you the shores a-crowding;

For you they call, the swaying mass, their eager faces turning

The title of the poem, ‘O Captain! My Captain!’ refers to Abraham Lincoln as a captain of the ship. Here, the “ship” is a symbol of the civil war fought for liberating the slaves. According to the poet, the ship is sailing nearer to the shore, meaning the war is about to end. They have achieved their coveted goal. Being a moment of victory, everyone is happy. However, they have to consider, at the same time, that their metaphorical “captain” of the ship is no more. When he lived, he guided the multitude with his fatherly guidance. After his death, the nation is fatherless. In this agony, the poet writes the verses. However, the mood of the poem is not gloomy. Even if they have lost Lincoln, the dream Lincoln has seen is not lost, according to the analysis of Poem Analysis.

The poem, ‘O Captain! My Captain!’ consists of 3 stanzas in totality having 2 quatrains in each. A quatrain is a stanza consisting of four lines. Besides, this poem is an elegy. An elegy is known as a mourning poem. Apart from that, Whitman uses the free verse form while writing this poem. For this reason, the lines of the poem do not rhyme at all. Yet there are some instances where one can find the use of rhyming. As an example, in the second part of the first stanza, the words “red” and “dead” rhyme together. Thereafter, the poet mostly uses the iambic meter in this poem. For instance, the first line is in iambic hexameter. The following two lines are in iambic heptameter. While the second quatrain does not follow a specific metrical scheme, cited by Poem Analysis.

3. “Invictus” by William Ernest Henley

|

| Photo: Rob Goll |

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds and shall find me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate,

I am the captain of my soul.

‘Invictus‘ is a Latin adjective meaning, “unconquered, unsubdued, invincible.” It is a combination of two Latin words, “in” meaning “not, opposite of” and “victus”. The word “victus” has come from the past participle of “vincere” meaning “to conquer, overcome.” Collectively the word “Invictus” means one who cannot be conquered, meaning unconquerable. However, the poem was published in 1888 in his first volume of poems, “Book of Verses”, without a title. Later the poem got reprinted in several 19th-century newspapers under various titles such as, “Myself,” “Master of His Fate,” “Captain of My Soul,” and “De Profundis.” The well-known title ‘Invictus’ was added to the poem by Arthur Quiller-Couch, the editor of the “Oxford Book of English Verse (1900).”, according to the analysis by Poem Analysis.

‘Invictus’, a Victorian poem, is made up of four stanzas and sixteen lines, with four lines in each stanza. It has a set rhyme scheme of abab cdcd efef ghgh. The poem also has a set metrical pattern. Each line of this poem contains eight syllables and the stress falls on the second syllable of each foot, a segment of two syllables. Hence the poem is written in iambic tetrameter. However, there are a few variations in the poem. As an example, the first feet of the first and second lines of the poem are trochaic. It means the stress falls on “Out” and “Black” in the first and second lines respectively. The rising rhythm of the poem sets an optimistic mood in the poem.

2. “She Walks in Beauty” by Lord Byron

She walks in beauty, like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies;

And all that’s best of dark and bright

Meet in her aspect and her eyes;

Thus mellowed to that tender light

Which heaven to gaudy day denies.

One shade the more, one ray the less,

Had half impaired the nameless grace

Which waves in every raven tress,

Or softly lightens o’er her face;

Where thoughts serenely sweet express,

How pure, how dear their dwelling-place.

And on that cheek, and o’er that brow,

So soft, so calm, yet eloquent,

The smiles that win, the tints that glow,

But tell of days in goodness spent,

A mind at peace with all below,

A heart whose love is innocent!

Scholars believe that ‘She Walks in Beauty‘ was written when Byron met his cousin Mrs. John Wilmont. She wore a spangled black dress, for she was in mourning, and the story goes that Byron was so struck by her beauty that he went home and wrote this poem about her, according to the summary by Poem Analysis.

It is written in iambic tetrameter, three stanzas of six lines each, which is a poetic form mostly used for hymns, and thus associated both with simplicity, and with chasteness. In fact, the poem itself, although a type of love poem, does not really refer to passionate or sexual love.

The speaker’s awe at the woman’s beauty comes across as just that: the awe that one would feel for a lovely painting, or a picture of nature. It is an especially unusual choice coming from Byron, given that he was mostly known for his lascivious affairs.

1. “Ulysses” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

It little profits that an idle king,

By this still hearth, among these barren crags,

Match'd with an aged wife, I mete and dole

Unequal laws unto a savage race,

That hoard, and sleep, and feed, and know not me.

I cannot rest from travel: I will drink

Life to the lees: All times I have enjoy'd

Greatly, have suffer'd greatly, both with those

That loved me, and alone, on shore, and when

Thro' scudding drifts the rainy Hyades

Vext the dim sea: I am become a name;

For always roaming with a hungry heart

Much have I seen and known; cities of men

And manners, climates, councils, governments,

Myself not least, but honour'd of them all;

And drunk delight of battle with my peers,

Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy.

I am a part of all that I have met;

Yet all experience is an arch wherethro'

Gleams that untravell'd world whose margin fades

For ever and forever when I move.

How dull it is to pause, to make an end,

To rust unburnish'd, not to shine in use!

As tho' to breathe were life! Life piled on life

Were all too little, and of one to me

Little remains: but every hour is saved

From that eternal silence, something more,

A bringer of new things; and vile it were

For some three suns to store and hoard myself,

And this gray spirit yearning in desire

To follow knowledge like a sinking star,

Beyond the utmost bound of human thought.

This is my son, mine own Telemachus,

To whom I leave the sceptre and the isle,—

Well-loved of me, discerning to fulfil

This labour, by slow prudence to make mild

A rugged people, and thro' soft degrees

Subdue them to the useful and the good.

Most blameless is he, centred in the sphere

Of common duties, decent not to fail

In offices of tenderness, and pay

Meet adoration to my household gods,

When I am gone. He works his work, I mine.

There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail:

There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners,

Souls that have toil'd, and wrought, and thought with me—

That ever with a frolic welcome took

The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed

Free hearts, free foreheads—you and I are old;

Old age hath yet his honour and his toil;

Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods.

The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks:

The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep

Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends,

'T is not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.

Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho'

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

Ulysses is a poem which gives us details about the unhappiness and monotony Ulysses is going through in his old age. He is living at his home on the island of Ithaca. The summary of Ulysses will take us through the monologue which he speaks in the poem. We learn that Ulysses is not content with the way of his life. In other words, he still wishes to continue sailing. However, he is getting old, but that does not stop him, according to summary and analysis of the poem by English Literature.

Ulysses believes that he must enjoy the little time left of his life. Moreover, he does not want to be busy dying but busy living. He always longs for that last sail of his life and imagines mariners as well. Thus, the summary of Ulysses will tell us all about his desires. In conclusion, he makes a resolution to continue to strike, seek, find but never yield.

Ulysses also imagines the sea calling out to him. He reminisces about the exciting travels he had together with his mariners. Their hearts and minds were free. Even though they are old now, they are still capable of doing noble deeds.

Even as the day ends, Ulysses still believes it is not too late. He years to discover a newer world and set ashore to sail. He wants to explore till his last breath and may even meet Achilles.

Ulysses concludes by thinking that although he’s old, his vigour is the same and has the same heroic hearts and strong will. Thus, he will always continue to explore and discover.

Top 10 Best Classic Poems For New Year Top 10 Best Classic Poems For New Year Have you ever tried reading classic poems on New Year holiday? Let’s explore Top 10 Famous Classic Poems For New Year. |

Top 15 Most Popular Poems For New Year Of All Time Top 15 Most Popular Poems For New Year Of All Time Reading, writing, and enjoying famous New Year poetry is a great past time. Check out top 15 most popular poems for New Year of all ... |

Top 25 Most Popular Poems for Thanksgiving Of All Time Top 25 Most Popular Poems for Thanksgiving Of All Time Check out the best Thanksgiving poems which can for devoting mother, father, parents, relative and to God. Take a moment to celebrate gratitude with these ... |

Top 30 Best Halloween Poems Of All Time Top 30 Best Halloween Poems Of All Time Scary Trick or Treat Poems for Halloween. If you are looking for some good poems on Halloween, you’ve come at the right place. |