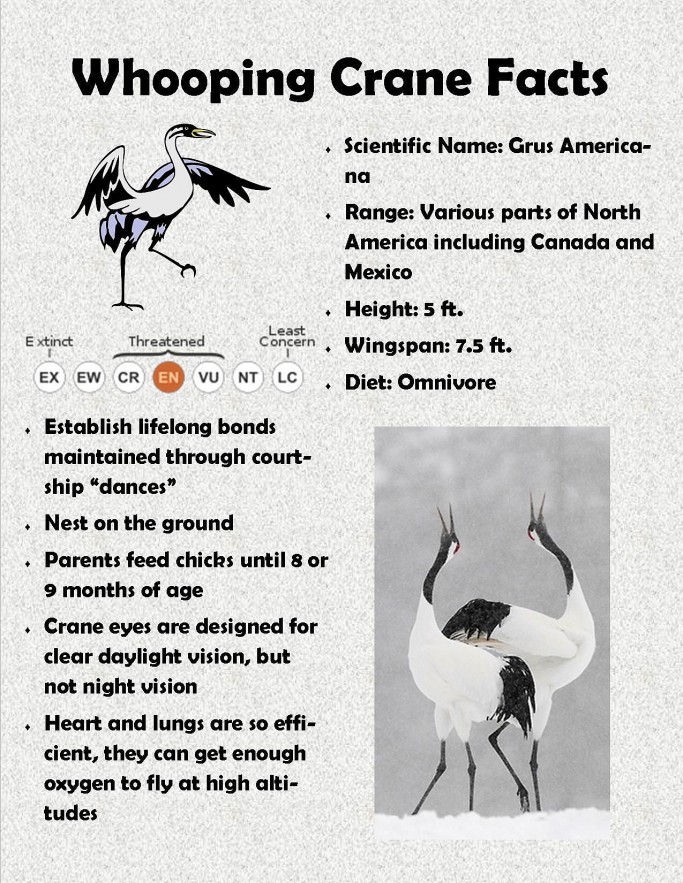

Facts About Whooping Cranes - Tallest and Rarest Birds In North America

|

| Facts About Whooping Cranes – Tallest and Rarest Birds In North America. Photo AP |

| Contents |

The Whooping Crane is the tallest bird in North America and one of the most awe-inspiring, with its snowy white plumage, crimson cap, bugling call, and graceful courtship dance. It's also among the rarest birds and a testament to the tenacity and creativity of conservation biologists. Why did they become rare? How big is a whopping crane? How long can a whopping crane live? You will find the answers right below!

How big is a whooping crane?

|

| Photo bird watching |

Weighing 15 pounds, the Whooping Crane has a wingspan of more than 7 feet and is as tall as many humans, reaching a height of around 5 feet. Also measuring 5 feet in length is its trachea, which coils into its sternum and allows the bird to give a loud call that carries long distances over the marsh. The Whooping Crane probably gets its name from either its single-note guard call or its courtship duet.

How does a whooping crane look?

Adult Whooping Cranes are identified by a red skin patch on their forehead, black “mustache” and legs, and black wing tips visible in flight.

| What do whoopers look like when they're flying? Their long necks are extended straight forward in flight, with legs extended beyond the tail. The wingbeat is slow. |

How is a whooping crane's body adapted to its lifestyle and habitat?

|

| Photo AP |

A crane has a very reduced back toe, so it won't get tangled in wetland vegetation, but this also means it can't perch in trees. A crane has a long, slender beak so that it can reach into deep water or through dense wetland vegetation to pull out crabs, plants, and other food on the bottom of shallow water. A crane's long legs allow it to see above tall, dense marsh vegetation. Such long legs help it walk in rivers and shallow lakes. Black tips on its flight feathers provide the pigments that strengthen the feathers right where they are most vulnerable to wear and tear in flight.

Whooping Cranes are very fast!While moving, the normal speed of an adult Whooping Crane is around 37-50 mph. They can reach speeds as high as 62 mph in the event that they have a tailwind to help them. A Whooping Crane in flight is an incredible sight. Whooping Cranes are omnivorous! Whooping Cranes are omnivorous and eat a wide range of wetland creatures. Their winter diets incorporate mollusks and blue crabs. In the late spring, they eat amphibians, frogs, small fish, and berries. While moving around, they mostly eat grain from farming fields. |

READ MORE: Only in the US: Whale Washed Ashore on Florida Coast Confirmed New Species

What is population of whooping cranes on Earth?

In 1941 there were only 21 Whooping Cranes left: 15 were migrants between Canada and Texas while the rest lived year-round in Louisiana. The Louisiana population went extinct, and all 600 of today’s Whooping Cranes (about 440 in the wild and 160 in captivity) are descended from the small flock that breeds in Texas.

Low population numbers, coupled with the loss of habitat and hunting pressures, nearly caused the Whooping Crane’s extinction in the early 1900s.

The only self-sustaining population of Whooping Cranes is the naturally occurring flock that breeds in Canada and winters in Texas. Three reintroduced populations exist with the help of captive breeding programs. One of these is migratory: researchers use ultralight aircraft to teach young cranes to migrate between Wisconsin breeding grounds and Florida wintering grounds.

As a result, Whooping Crane populations now total approximately 650, including a wild population that migrates between Canada and Texas; three introduced populations; and a captive group of 160 birds.

The Whooping Crane is an endangered species!Whooping Cranes were pushed extremely close to termination because of hunting and environmental misfortune. There were just 21 of them left in the wild by 1941. As a result of the endeavors of different associations, there are currently about 800 Whooping Cranes on the planet, including wild and hostage birds. Luckily, their populations are bouncing back. The Endangered Species Act of 1973 was instrumental in improving the Whooping Crane population. |

| Good news is: The Whooping Crane population has bounced back significantly! The Whooping Crane is one of the two local North American types of Cranes. The number of birds in this species fell radically to where they were nearly extinct. However, now they are flourishing again and can be found in Canada, Wisconsin, some midwestern states, Louisiana, and Florida. They are transient birds who winter in the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas and Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada. |

How old is a whooping crane?

A whooper in the wild usually lives 24-30 years. A Whooping crane in captivity may live 35 to 40 years or even longer. On June 2, 2007, a crane named "Rattler" at at the Internationl Crane Foundation (ICF) broke the record for longevity of a Whooping Crane in captivity! Rattler hatched at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland on June 2, 1968 and lived there until 1989. He was given special food treats all during his birthday week to celebrate, and the aviculturalists ate cupcakes for Rattler's birthday party. The previous record for a captive Whooping crane was 38 years, 7 months for "Canus." This injured wild-caught chick died at Patuxent WRC in 2003. Banding studies help us learn how long cranes live, but voice prints are the newest way way of keeping track of individual cranes over the years.

| The oldest Whooping Crane on record—banded in the Northwest Territories in 1977—was at least 28 years, 4 months old when it was found in Saskatchewan in 2005. |

Whooping crane's unique characteristics

|

| Photo Pinterest |

The sight of a pair of these magnificent white cranes flying over the quiet solitude of a northern marsh or prairie is unforgettable. When the weather is good and the winds favourable, a migrating Whooping Crane flies like a glider, on fixed wings. The bird spirals upwards (aided by thermal activity), glides down, dropping as low as 70 m above ground, and then begins spiralling upwards again. This spiralling and gliding, carried out when the cranes encounter suitable thermal updrafts, is energy efficient and allows the cranes to fly nonstop for incredible distances.

From 1977 to 1988, wildlife biologists captured 134 70-day-old juveniles on the breeding range, attached brightly coloured plastic bands, and then released them. These markings have allowed biologists to identify individual cranes in the wild and to learn about the life history of Whooping Cranes. During 1981, 1982, and 1983, 15 of the juveniles were also equipped with small radio transmitters that enabled Canadian Wildlife Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service staff to track cranes and obtain detailed information on their migration. They learned that average daily flight distance, flight duration, and ground speed are normally about 400 km, 7.5 hours, and 53 km per hour, respectively; and that nonstop flights of 10 hours, covering 750 km, are not unusual. In 1984, they tracked a crane wearing a radio transmitter at a record wind-assisted ground speed of 107.5 km per hour. They observed most migrating whoopers at altitudes below 600 m above ground level, but they found that high altitude migration was not unusual. The highest recorded flight was 1 950 m.

What does a whopping crane eat?

Wintering Whooping Cranes prefer blue crabs and several types of clams, but they also eat crayfish, small fish, snakes, insects, acorns, and small wild fruit.

During the summer, family groups spend their time in the shallows of small ponds and marshes. Here the adults perhaps find larval, or inactive, forms of insects such as dragonflies, damselflies, and mayflies, and also snails, small clams, water beetles, leeches, frogs, and small fish to feed their young. When the parent birds kill larger prey, such as snakes, mice, small birds, duck

lings, and even birds up to the size of half-grown bitterns, they share these with their young.

What are rarest birds in the US?

In just the last 50 years, nearly a third of all U.S. and Canadian birds have disappeared. As it stands, one out of every eight bird species in the world faces extinction.

But that doesn't mean all birds are in trouble: Population declines are disproportionate, making some birds much rarer than others.

Birds in the United States are no exception: We've already lost a number of species to extinction and are close to losing more. While there are many birds with limited or declining numbers that could be considered “rare,” we highlighted only those species with the smallest populations in the continental U.S. — the rarest of the rare — ranking them by population from largest (relatively speaking) to smallest.

Most of these birds are surviving thanks to the heroic, decades-long efforts of conservationists. But that doesn't mean the work is finished: The future of these rare birds depends on our commitment to their long-term survival. To learn more about how you can help birds, make sure to continue scrolling below our list. You'll also find more information about the data used and how we compiled this list.

Gunnison Sage-Grouse (Centrocercus minimus)

The Gunnison Sage-Grouse holds special distinction as the first new bird species formally described to science in the United States since the 19th century. But this federally Threatened species isn't new: It and the Greater Sage-Grouse were assumed to be the same bird until 2000, when they were officially split into two species, based on differences in their behavior, physical attributes, and vocalizations.

Kirtland's Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii)

Of the more than 50 warbler species found in the U.S. and Canada, none have ranges smaller than the Kirtland's Warbler. That's because these rare birds have very specific needs when it comes to choosing breeding grounds: They almost exclusively inhabit large, dense stands of young Jack Pine in Michigan (as well as nearby areas of Wisconsin and Ontario).

Island Scrub-Jay (Aphelocoma insularis)

Found on a single island off the coast of southern California, the Island Scrub-Jay has the smallest range of any North American bird species and, not surprisingly, one of the smallest populations. Once thought to total more than 12,000 individuals, the population of this Near Threatened species is now estimated to be only 2,300. Genetic evidence suggests that the Island Scrub-Jay diverged from the California Scrub- Jay, its closest relative (and a widespread species), 150,000 years ago.

California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus)

The California Condor isn't just the largest bird in North America, it's also the rarest. Although these Critically Endangered birds once roamed much of prehistoric North America, their population dwindled to a mere 22 birds in the 1980s. In years past, the condor's decline was fueled by hunting as well as poisoning from strychnine and lead ammunition found in the carcasses these scavenging birds consumed. While hunting and strychnine are no longer the species' main threats, lead poisoning remains a significant danger.

Bird's Nest - Top Weirdest Drinks in the World Bird's Nest - Top Weirdest Drinks in the World Top Weirdest Drinks in the World: Bird’s Nest Drink is considered as a breakdown of the ancient delicacy. Why does it have such a ... |

How to Take Care of Your Pet Birds How to Take Care of Your Pet Birds Birds are beautiful creatures. They are both entertaining and fun to play with - but at the same time allow you to 'get on with ... |

What Is The Biggest Flying Bird On Earth What Is The Biggest Flying Bird On Earth In ancient times, on earth there were many large flying that they could almost rule the whole world. Even humans were not their opponents. What ... |