What is the First Song Ever Recorded in History ('Au Claire De La Lune')

|

| Au Claire De La Lune |

The first recorded song was never meant to be played back!

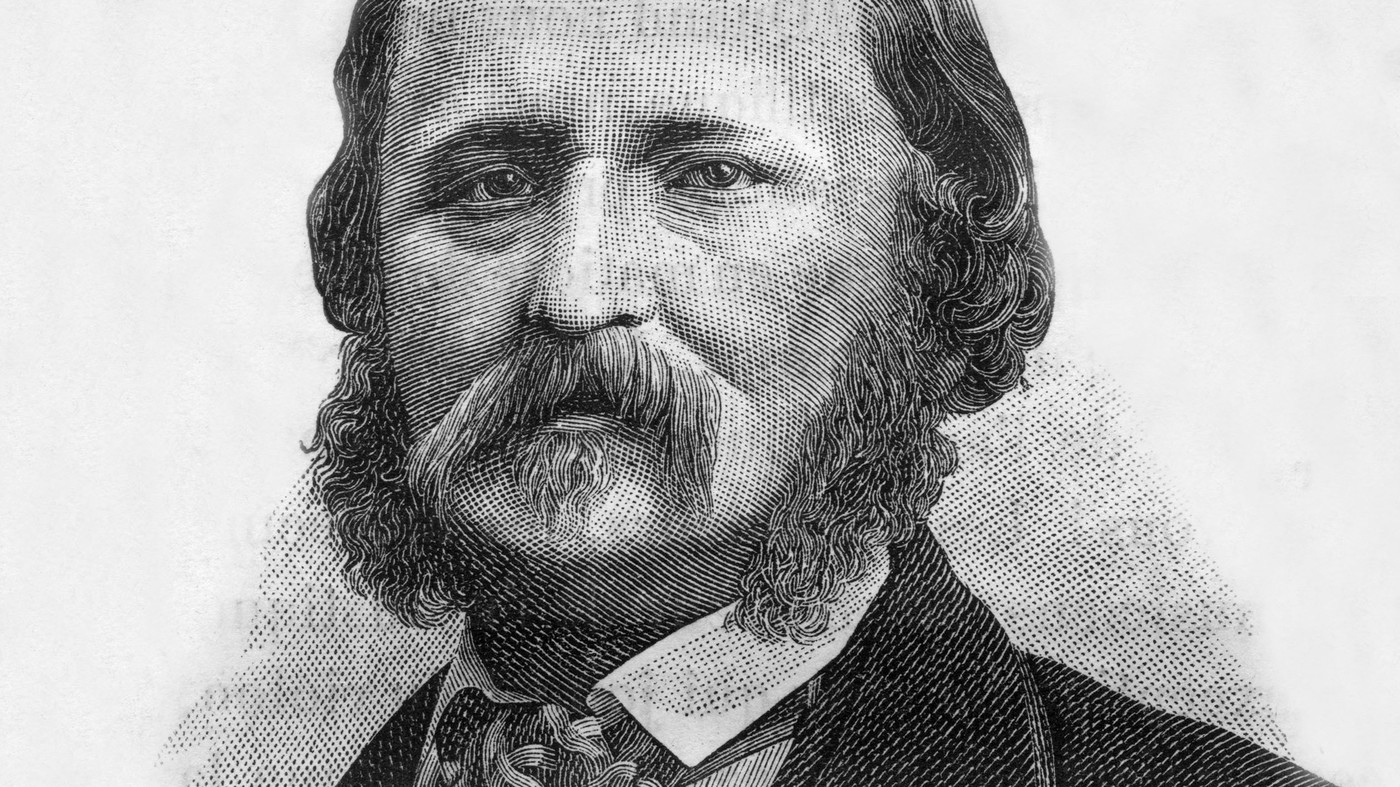

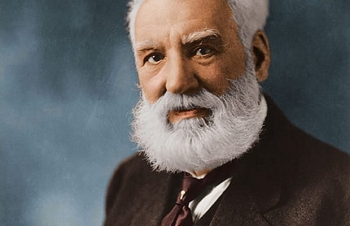

The answer to the question of what sound was the first to be recorded appears to be fairly obvious. It was photographed in Paris by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville in the late 1850s, more than 20 years before Thomas Edison invented the phonograph (1877) or Alexander Graham Bell made the first telephone call (1876).

|

| Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville. Photo: NPR |

This recording, which was only recently found, is thought to be the earliest known instance of a human voice. Au Clair de la Lune is actually an 18th-century French folk song. In 1860, Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville used a phonautograph to record a woman singing a few lines of this song. Prior to Edison, Scott de Martinville discovered how to record sounds, but he was unable to figure out how to play them back.

Over a century later, in 2008, the recording was restored to sound, according to CataWiki. Amazing, though the recording is a little eerie and scratchy, as if the voice from a century ago is struggling to be heard.

Importantly, though, Scott didn't believe anyone would ever hear the recordings he made while he was recording the sound. He believed they would read the tracings instead. The first sound that was recorded was thus different from the first sound that was played back from a recording. The second turning point wouldn't occur until the age of Edison.

According to audio historian David Giovannoni, "Scott never considered the possibility of putting those signals back into the air, and no human on the planet did until 1877. Nevertheless, those sounds are still audible today thanks to the First Sounds collaboration, which Giovannoni helped found in 2008. It's also important to keep in mind that Scott's recording was artificial, capturing sound that was changing over time and coming from the air; other types of sound recordings existed before his experiments.

How 'Au Clair de la Lune' was recorded?

What precisely did Edward-Léon Scott de Martinville document? Which of Scott's recordings were successful enough to count will determine the answer.

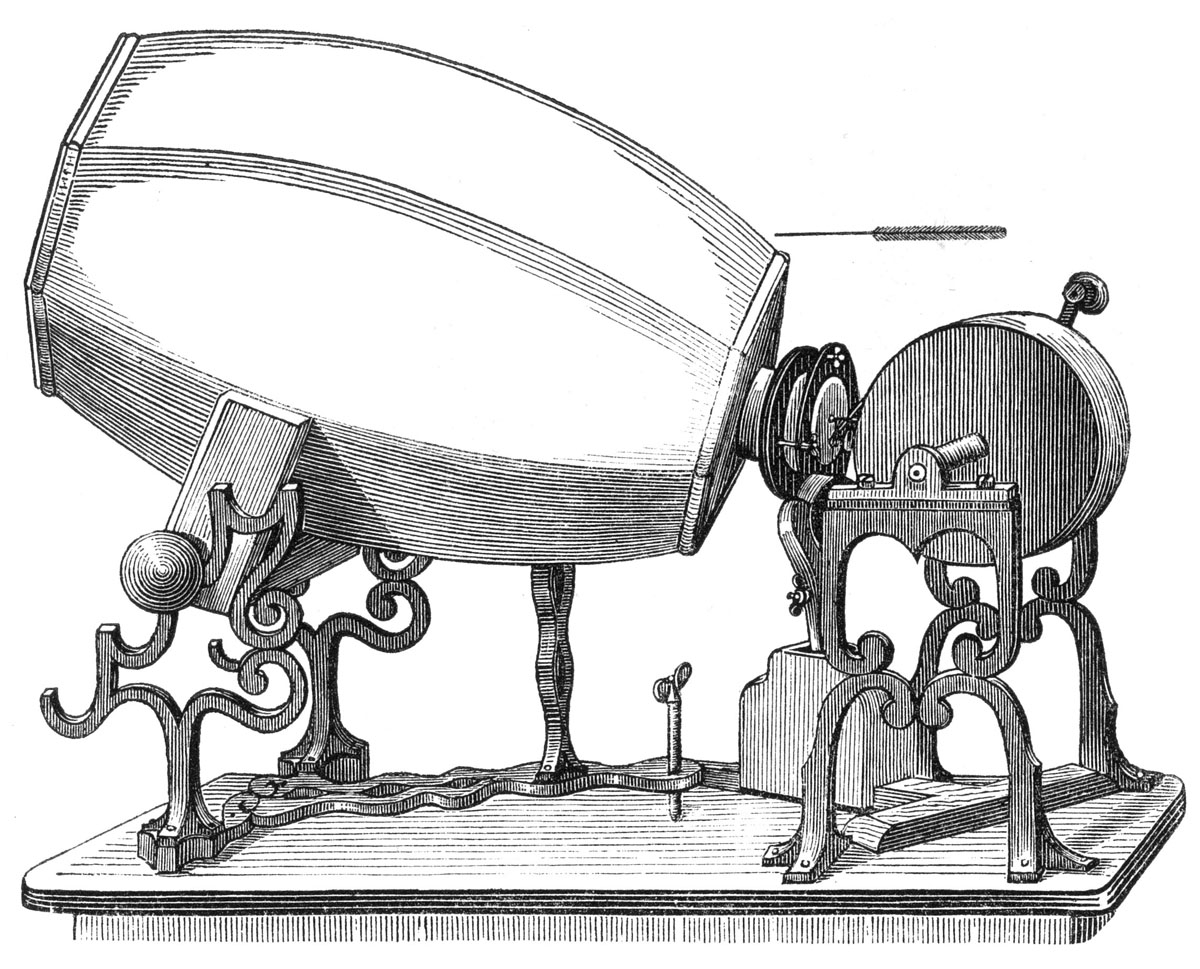

Although he wasn't a scientist or inventor by trade, he had ambitions to enter those fields. By 1853 or 1854, he had a breakthrough: he reasoned that if a camera can replicate an eye to fix an image to paper, some sort of mechanical ear could do the same for sound. He used the daguerreotype as his model. The phonautograph is the name Scott gave to his creation.

|

| Photo: The Atlantic. |

A thin stylus with an attached vibrating membrane that served as the eardrum could be used to track the movement of the membrane. Scott could record the fine, wavy trail it left by smearing a piece of paper or a glass plate in soot and moving it beneath the stylus. Those lines, which are essentially an image of the sound wave, could be interpreted by a skilled reader to reveal what the sound was.

That was the plan, at least. Even today, though aspects of sound like pitch or amplitude are somewhat visually interpretable in audio-editing software, it's not really something people can do. It turned out to be much harder than Scott anticipated for people to read words from images of sound waves.

Though Feaster notes that the recordings are extremely brief and "so crudely done that it's not really clear these really count as sound recordings," his early efforts are documented.

In a manuscript that he submitted to the French Académie des Sciences in January 1857, Scott described his research and some of his earliest recordings as well as his hopes for the future of the phonautograph. It might use a "automatic stenographer" to transcribe conversations or record actors or singers. Will the writer's improvisation, which usually appears in the middle of the night, be able to be recovered the following day with its freedom, this total independence from the pen, an instrument which is so slow to represent a thought which is always cooled in its struggle with written expression? Scott had faith that it would occur. He submitted a patent application that year, as stated by

He switched from recording on a straight sheet of paper or glass to one that was wrapped around a cylinder as he improved the recording apparatus. This allowed for longer recordings, but because he was still moving the apparatus by hand, timing was irregular. He recorded a tuning fork alongside the other vocalizations and sounds in 1859 and 1860. Giovannoni, Feaster, and other members of the First Sounds collaboration were able to accurately calibrate the time and restore the recordings' recognizability thanks to the predictable vibration rate of a turning fork. On April 9, 1860, Scott captured a brief excerpt of the French folk song "Au Clair de la Lune."

As a result, the precise "first recorded sound" would occur somewhere between the earliest experiments and the well-known "Au Clair de la Lune" record. (On the First Sounds website, you can listen to recordings from 1857, 1859, and 1860.) However, due to the severe speed irregularities, it is difficult for modern researchers to determine with certainty whether the early recordings were successful or which one should be considered the first.

Due to the lack of playback technology at the time, it was even more difficult to determine. Scott found himself in the peculiar situation of being essentially unable to demonstrate that his invention worked. In the end, he abandoned the project and didn't pick it back up again until Edison made headlines toward the end of his life.

Giovannoni refers to Scott's hopes that the sound waves could be visually read as a "sense in which he failed." "In another sense, he was wildly successful. The first device to continuously record sensory data in real time was the phonautograph.

| Some researchers did recognize the potential of phonautography; Rudolph Koenig, a maker of acoustic research instruments, sold a model until 1901, and Alexander Graham Bell used a phonautograph variant to record some vowel sounds in 1874. |

What is the First Telephone in the World and Who is Inveted it? What is the First Telephone in the World and Who is Inveted it? Have you ever wonder what is the history of the first telephone in the world. If your answer is yes, you landed on the right ... |

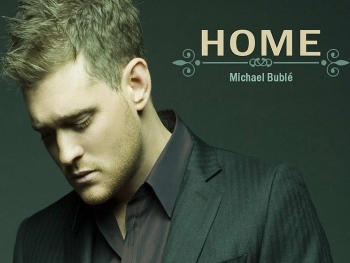

Family's Songs: Full Lyrics of 'Home' - Michael Bublé Family's Songs: Full Lyrics of 'Home' - Michael Bublé "Home" is a song recorded by Canadian singer Michael Bublé, and released on January 24, 2005, as the second single from his second major-label studio ... |

SPUTNIK V UPDATE: First registered COVID-19 vaccine in the world SPUTNIK V UPDATE: First registered COVID-19 vaccine in the world Russian adenovirus vector-based vaccine - Sputnik V - was registered by the Russian Ministry of Health on August 11 and became the first registered COVID-19 ... |